|

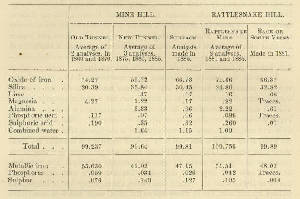

CHAPTER XXIII. DURHAM TOWNSHIP. IN the extreme northeastern part of Bucks county, a nearly rectangular area about ten square miles in extent is inclosed between Northampton county and the Delaware river on the north and east, and Nockamixon and Springfield on the south and west, differing widely from the surrounding country in the nature of its resources, the circumstances of its settlement, and the characteristics of its population. It is a region of great natural beauty. Durham creek flows through the valley of this name, which is about two miles in breadth, bounded on either side by high hills, the ascent of which is sufficiently gradual to permit cultivation almost to their summits. From the highest point of one of these elevations the observer beholds a scene spread out before him which rivals the most famous landscapes in this country. The protecting convolutions of South mountain form the northeastern horizon; while spurs of every variety of contour, elevation, and direction radiate from the primary range. The Delaware sweeps into view at a point to the north, gradually widening in its approach until it becomes the broad expanse of water immediately beneath the observer’s gaze. Following its course to the southeast, it describes a bold, semicircular curve, entering the "Narrows" beneath the shadows of overhanging and perpetual foliage. These rocks of new red sandstone rise in perpendicular bluffs about three hundred feet above the level of the river, comparing favorably in height with the famous "Palisades" of the Hudson. There are evidences of the existence of the prehistoric man in these cliffs that line the Delaware. It does not require any great effort of the imagination to conceive of a rounded stone having been used as a hammer, a sharply pointed one as the point of an arrow or a spear; a cave may have been a habitation, and the loose fragments of its rocky sides the implements and weapons of primeval man. The progress of his rude civilization through the successive periods of the stone, bronze, and iron ages can be as clearly traced in the cabinet of the archaeologist as the political development of the races that have succeeded him from the records of the historic page. The frequent discovery of Indian relics suggests the occupation of the Indian race. The location of several towns in Durham has been accurately determined by the presence of these silent but interesting relics of former generations. The site of an extensive village has been traced from the Riegelsville Delaware bridge southward as far as the Durham iron-works, and inland a distance of a half-mile with the course of Durham creek. The remains of earthen fireplaces, pottery, and stone implements were quite numerous a half-century since, but have steadily disappeared under the frequent drafts of relic-hunters. This town existed in 1727 under the name of Pechoqueolin, at which time it was presided over by a chieftain, who bore the euphonious name of Gachgawatchqua. He was accountable for the deeds and misdeeds of his people to the Lenni Lenapes, and held the land by a tenure which bore some resemblance to the feudal system of the middle ages. His people were Shawanese. They were a brave, active, turbulent, and warlike people. They seem to have been comfortably established here. About a mile west from the principal town, on an elevated plateau, was an opening in the forest about seven acres in extent, still remembered by the older citizens. It is remarkably free from the loose stories scattered promiscuously over the surrounding fields. It is supposed that this was an Indian corn-field. In support of this theory it may be stated that the soil within well-defined limits had apparently been exhausted by years of cultivation before the arrival of the German farmer who first applied the plow, and endured the disappointment of ill-requited toil. To the west of this about two miles, on the second spur of the South mountain and overlooking Fry’s run, there is another traditional Indian field. Its area is about five acres, and it was completely circumscribed by a dense forest until 1875. About the center stood a solitary tulip-tree, fully five feet in diameter. Numerous little mounds or ridges everywhere mark the effects of cultivation by the Indians. These mounds have been observed throughout the west, and are seen in the corn-fields of the Indians today, where the plow has not superseded the use of his simple implements. The ostensible occasion of their residence at Pechoqueolin is explained by James Logan, who states in one of his letters that, upon their arrival from the south, "they were placed by the Delawares at such places where there was something to watch over." One band was sent to Wyoming to guard the supposed silver mines there; another was stationed in the Minisinks near Stroudsburg to guard the copper ore; and a third division was intrusted with the protection of the iron of Durham. This was in 1698. It has been inferred from this that the existence of iron ore here was certainly known at this time; and it seems probable that the mining of ore had been begun equally early, but such supposition is purely a matter of conjecture. It had already enlisted in its development the efforts of a powerful London syndicate, "The Free Society of Traders." The powers and privileges conferred by Penn upon this remarkable corporation were most unique. It was organized in March, 1682, with Nicholas Moore as president, and received a grant of twenty thousand acres of land, which were to constitute "The Manor of Franks." Officers of the province were restrained from interfering with its affairs. Taxes were to be assessed and collected within the manor by such process as its officers should direct. It was stipulated in behalf of the proprietary that the society should establish factories, transport tradesmen and artificers, manumit slaves after fourteen years’ service, and signify their allegiance to him by the payment of one shilling annually upon the day of the vernal equinox. Five thousand acres of the grant of 1682 were surveyed at some time before the close of that century, and located under the name of Durham, comprising the whole of the township of that name and a considerable area in Northampton county. The seating of a tract of land fifty miles distant from any important settlements when it could have been procured in the vicinity of Philadelphia at equal cost, and possessing the advantages of greater fertility and accessibility, proves conclusively that the mineral resources of the region were already known. One hundred men were to be sent to Durham; but there is no evidence in regard to the carrying out of this plan. In a metrical composition entitled "A Short Description of Pennsylvania," which appeared in 1792, the author, Richard Frame, states "that at a certain place about some forty pounds of iron had been made." No particulars as to where, or how, or by whom this was done are given. In the history of New Albion, published in 1648, allusion is made to the existence of lead in the hills some distance above the falls of Delaware. The Indians early learned the nature and value of that metal. It is possible that their information on the subject induced investigation and led to the discovery of iron. And thus in the wealth of the mineral resources of its hills is found the explanation of the comparatively early settlement of Durham. The recorded history of the furnaces dates from the year 1727. On March 4th of that year a stock company was formed for the purpose of working iron, by Jeremiah Langhorne, Anthony Morris, James Logan, Charles Reed, Robert Ellis, George Fitzwater, Clement Plumstead, William Allen, Andrew Bradford, John Hopkins, Thomas Linsley, Joseph Turner, Griffith Owen, and Samuel Powell. These persons had succeeded to the interests of the Free Society of Traders, who derived their title from the Indians direct before their right had been extinguished by formal purchase of the constituted authorities. An act of assembly was passed in 1700 declaring void all subsequent private purchases. The fact that Teedyuscung acknowledged this purchase and the title of the society to their land proves that it must have been acquired before that time. If any iron was made by them, it must have been in blomaries, as no furnace was in existence at the time of the formation of the new company in 1727. The first furnace of which anything authentic is known was put in operation in that year. It occupied the site of the mills of R.K. Bachman & Bro. on the Durham creek about one mile and a half from its mouth, and in the center of a rich metalliferous deposit. It is said to have been between thirty-five and forty feet square and about thirty feet high. The casting-house was built of stone, facing toward the west. Upon the site of Bachman & Bro.’s store was the stamping-mill, a building in which the cinders were crushed and the iron that had been wasted with the slag was separated from it. In digging the foundation for the grist-mill, the workmen encountered a huge lump of iron ("salamander") of about six to eight tons in weight, which had evidently escaped from the furnace through the hearthstones. All endeavors to remove it proving futile, they were at length compelled to dig a pit at the side and thus lower it out of their way. The water-power of the creek was utilized in various ways, principally in operating a number of forges and in working an enormous bellows that produced the blast. The dam was situated about a mile farther up the creek, and the timbers constituting the dam in the bed of the stream are still sound and may remain so for another century. The course of the race can still be plainly traced. There were three forges along the creek, all below the furnace. The uppermost was situated about a half mile distant from it, where the foundations are still distinguishable, and the cinders and debris were screened about forty years ago. The middle or second forge was located about the same distance farther east, and its foundations can also be traced. The third, of which every vestige has been obliterated, occupied a site near the present furnace. In addition to these, numerous forges elsewhere were also supplied, among which were those located at Mount Pleasant, in Berks county; Chelsea, on the Musconetcong creek, one mile northeast of Riegelsville, New Jersey; Changewater, near Washington, N.J. on the same stream in Warren county, New Jersey, ten miles east of Belvidere; Greenwich, near Chelsea; Green Lane, on the Perkiomen, in Montgomery county. Another industry already associated with the furnaces was the burning of charcoal. The improved methods now in vogue had not then been introduced. That it was an important industry may be inferred from the number of pits of which the remains may yet be seen in the valleys of the Durham and Musconetcong. In those early times, when the howling of the wolves broke the stillness of the forest, and the red man was the frequent visitor of his white neighbor, the occupation was interesting and adventurous as well as lonely and dangerous. The method usually employed consisted in selecting a location easy of access and sheltered from the prevailing winds; the site chosen was carefully levelled and a stake was driven into the ground with a height of a foot or more above the surface, around which a quantity of small wood to ignite the pile was placed until it attained a radius of two or three feet from the stake. Horizontal layers were added to this to the height of nine or ten feet, thus forming an opening for a chimney. Outside of this and inclining inwards the material of the pit was placed in vertical layers until it attained the required size. The whole of the exterior surface was then covered with turf. While in process of burning or charring the pit required constant attention during a period ranging from seven to ten days. The process reduced it to about half its original size. The charcoal was then hauled to the furnace in wagons drawn by four and six horses. Such, in brief, was one of Durham’s "lost arts." The manufacture of stoves may be classed in the same category. As far as known, the earliest effort to dispense with the open fire-place, once universally in use, and to substitute an appliance similar to the common stove, was made in 1678 by Prince Rupert of England. It was he who first demonstrated the feasibility of applying heat through the medium of a radiating surface. The most important improvement upon this was made by Dr. Benjamin Franklin. The following instructions, written by himself, were given to those who should use his stove: "To use it, let the first fire be made after eight o’clock in the morning or after eight o’clock in the evening, for at those times there is usually a draft up a chimney, though it has long been without a fire; but between these hours in the day there is often in a cold chimney a draft downward, when, if you attempt to kindle a fire, the smoke will come into the room; but to be certain of your time, hold at the top of the base over the air-hole a piece of lighted paper. If the flame draws strongly down, the fire may be lighted." Franklin perfected his invention in 1745. The published account of it gives abundant and conclusive reasons why those previously in use should be abandoned in its favor. It does not appear whether the Durham proprietors secured the right to manufacture it or not, but from 1745 to 1791 a stove combining its advantages with such improvements as experience proved necessary was manufactured by them to an extent sufficient to give the works a wide reputation. The Franklin stove sold at the furnace for four pounds ten shillings. The Philadelphia stove, a contemporary innovation, was disposed of at the rate of eighteen pounds per ton, the price varying with the cost of the material of which it was made. In 1790 a Mr. Pettibone, of Philadelphia, patented a heating apparatus for use in churches, halls, hospitals, and similar large rooms. It is not probable that many of these were made at Durham, as the furnace blew out the following year. The earliest pattern of a stove known to have been made here was called the "Adam and Eve," from the character of the embellishments on its side. The date, 1741, is inscribed in raised characters, and in the background appears a representation of Adam, Eve, the serpent, several animals and trees well executed and in good artistic taste. The Back-house pattern, so known from the proprietor of the works during the revolution, was the most popular among those who used it. It combined the fixtures of a heating, baking, and cooking stove. The most superbly finished pattern was that made by George Taylor, who had an elaborate model constructed with the inscription, "Durham Furnace, 1774," that being the year in which he assumed control of the works the second time. A portion of a stove bearing this inscription was to be seen for many years in front of the post-office at Easton in a conspicuous position. A noticeable peculiarity in connection with this branch of the iron business is the fact that shipments were always made by land and never by boats, when the consignment was to Philadelphia. It required a full week for a team of four or six horses to make the journey to the city and return. And yet, under a combination of unfavorable circumstances such as this, the requirements of the age were fully met as far as Durham stoves were concerned. The machinery that could thus be adapted to the peaceful pursuits of the people could be used with equal success in furthering their efforts when at war. The shipments of shot and shell during the month of November, 1780, when the revolution was drawing to a close, amounted to upwards of two tons, and the price was twenty-five pounds per ton; the total value of shipments during the year was one thousand and seventy-six pounds one shilling two and one-half pence. In the following year, the different consignments of shot and shell for the continental army aggregated in value one thousand nine hundred and eighty-two pounds eight shillings eight and one-half pence. The product throughout the war was correspondingly large. A large proportion of the shot were three and nine pounders, but double-headed shot were also cast and shipped. The shell weighed from twenty to sixty or more pounds apiece. In 1782, August 12th to 17th inclusive, twelve thousand three hundred and fifty-seven solid shot, ranging in weight from one ounce to nine pounds, were shipped to Philadelphia. Mementoes of this stormy period are yet to be found in the cabinets of persons interested in local history. The course of events during this period was marked by important changes in the ownership, management, and control of the furnaces. The copartnership of 1727, although originally intended to continue fifty-one years, was dissolved by mutual consent some time before the expiration of that period. To facilitate a division of the property, the eight thousand five hundred and eleven acres one hundred perches composing it were divided into forty-four tracts of varying size; and in the allotment which followed, tracts numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 33, embracing the site of the furnace and forges, and the principal sources of ore, became the property of Joseph Galloway and Grace his wife, and was confirmed to them in a deed of partition executed December 24th, 1773, to which are affixed the names of the Galloways, Abel James, John Thompson, trustees of Thomas Nickleson, and Elizabeth his wife; Joseph Morris, and Hannah his wife; the Honorable James Hamilton, Cornelia Smith, relict of George Smith, and James Morgan, an iron-master. Joseph Galloway thus became the first individual proprietor of Durham Furnace. He was born in Maryland in 1730, of respectable parentage, but removed to Philadelphia in early life, and engaged in the study and practice of law, but after marrying Grace Growden, the daughter of Lawrence Growden, proprietor of Trevose, he made the latter place his residence. He was a man of fine talents, but lacked strength of character. During the earlier troubles with Great Britain, he was prominently, and probably sincerely, identified with the interests of his native country. But when misfortunes and reverses appeared upon the American political horizon, he proved unworthy of the cause he had espoused, joined the British at New York, and became the persistent defender of the crown. By act of assembly of March 6th, 1778, he was required to surrender himself under pain of being attainted of high treason. He deemed it advisable for his personal safety not to comply with the mandates of the law, and was accordingly attainted, and his estates declared forfeited to the commonwealth. Richard Backhouse succeeded to the title thus vested in the State authorities, but his possession was of short duration. Legal complications ensued, the heirs-at-law of Galloway protesting that his property had been acquired by marriage, and was not therefore subject to seizure as the penalty of treason, as his wife had not shared his political views. The courts decided adversely to Backhouse,* whose heirs were dispossessed in 1799, when Elizabeth (Galloway) Roberts succeeded to the possession of the property. Her daughter, Grace Ann (Roberts) Burton, was the next owner of the furnaces. She died in 1837, when her son, Adolphus William Desart Burton, became proprietor under his mother’s will. He was the last descendant of the Growdens in whom the title to their ancestral estates was vested. During this time the management and operation of the works were principally intrusted to lessees or superintendents. The James Morgan, "ironmaster," and owner of a sixteenth interest in the works, prior to the partition sale of 1773, was one of the latter class. The son, General Daniel Morgan, rose to distinction as a revolutionary soldier. He was born in Durham township in the winter of 1736, and has justly been given the place of honor as the most distinguished of her citizens. In early life he assisted his father in the multitudinous duties of his position. He began his military career as the driver of a baggage-wagon in the disastrous expedition of 1755 against Fort Duquesne, having run away from his home two years previously. The following year he held an ensign’s commission, and endangered his life on several occasions while the bearer of important despatches. In one instance, when accompanied by two companions, both were killed by an Indian ambuscade, while he escaped with a wound in his cheek, and the loss of several teeth. At the close of the seven years’ war he married, and engaged in agricultural pursuits in Clark county, Va., where he remained until the outbreak of the revolution, when he recruited the famous brigade known as "Morgan’s Riflemen," from among the backwoodsmen of Virginia and western Maryland. Their achievements at Stillwater and Cowpens have received merited praise from the most competent military critics. But the exposure and privations of repeated campaigns at length affected the iron constitution of their gallant commander. He returned to his home upon the cessation of hostilities, was elected to congress, but resigned before the expiration of his term. He died at Manchester, Virginia, July 6, 1802, at the age of sixty-seven years. A scarcely less distinguished personage, whose connection with the furnace was still more intimate, was George Taylor, a signer of the declaration of independence. He was born in 1716, the son of an Irish clergyman, who designed to educate him for the medical profession. His nature was not adapted to the pursuit of a calling requiring such assiduous attention, and he deserted his studies at the earliest opportunity, taking ship for America as a redemptioner. Arriving at Philadelphia, he indentured himself to Nr. Savage, the lessee of the Durham works at that time, who paid the expenses incurred on his voyage. He accompanied Mr. Savage to Durham, there to redeem the money thus advanced by labor scarcely as pleasant as studying medicine. He was employed for some time as a "filler," but, giving evidences of intelligence and ability, was promoted to the position of clerk, and eventually became a member of the firm. Upon the death of his employer, in 1738, he married his widow, and became sole lessee of the Durham iron works. He again assumed control from 1774 to 1779, during the ownership of Galloway. He amassed a considerable fortune, and was interested in industrial pursuits of a varied character at other places. He early manifested an interest in provincial politics. He represented Northampton county in the assembly for the first time in 1765, and again on several occasions. In 1763 he was appointed treasurer of a board of trustees which superintended the erection of a court-house at Easton. In June, 1766, he was one of a committee which drew up the remonstrance against the "Stamp Act." He was a member of the continental congress of 1776, and in that capacity signed his name to the declaration of independence. The following year he was active and energetic in urging the legislature of Pennsylvania to provide for its defense against threatened invasion. In March, 1777, he retired from public life. His death occurred February 23, 1781. One of the most prominent objects in the Easton cemetery is a graceful shaft of Italian marble, the pedestal of which bears the arms of the state of Pennsylvania, while the American flag, draped in crape, is suspended at the top. It was dedicated to the memory of George Taylor November 20, 1855, with proper civic and military observances. The work is both significant and appropriate. It recalls the worth and public services of a useful citizen and an unswerving patriot. The construction and appearance of the furnaces changed with much less frequency than their proprietors. Tradition asserts that iron was made at Durham long before the works of 1727 were erected; and if this be true, it may safely be assumed that the blomary or stuckofen was in use for this purpose. The process of smelting was attended with much difficulty (owing to the crude process thus employed) and without the knowledge of chemistry. The operation was frequently repeated several times, in order to secure a product free from cinder and other foreign substances. In the transition from the primitive machinery at first used to modern appliances, the first step was increased height in the blomary. One of the two blomaries in operation in 1750 was probably erected on this principle. It was about ten feet high, with an opening about two feet square in front and another three feet in diameter on top. The former was not closed until the blast had been applied, when the charcoal and ore were thrown in at the same time. The product was a mass of conglomerate iron and steel, malleable, and yet more fibrous and dense than is usually produced at more modern furnaces. The annual product of a blomary of this character was about one hundred and fifty tons. The weekly capacity of the regular furnace was twenty-five tons. The furnace of 1727 was in operation from that year until 1791, with occasional intervals of suspension from various causes. The following extract from Richard Backhouse’s journal shows some of these causes during his administration: "Tuesday, May 30, 1780; at eleven o’clock in the morning, Durham Furnaces began to blow. July 18, Tuesday, at 3/4 after three o’clock, blew out— blew seven weeks. September 1, 1780; Friday night, at half after ten o’clock, began to blow. November 15, Wednesday morning, at ten o’clock, blew out— blew ten weeks and five days. Sunday morning, May 13, 1781, at 10 o’clock Durham Furnace began to blow. June 18, Monday morning, stopt up for want of coals occasioned by the excessive floods of rain. June 25, Monday morning, began again to fill with mine, etc. 27, Wednesday morning about 7 o’clock, the mine came down. July 17, Tuesday at 8 o’clock in the morning, blew out. June 9, 1782, Sunday morning at 4 o’clock, began to blow. December 10, 1782, at four o’clock in the afternoon, the furnace blew partly off, and then finished by heaving off the rest, as the wheel froze fast— blew 6 mo. 1 week. Put fire in the furnace on Thursday, May 15, 1783, about three o’clock in the afternoon; put on mine Saturday about 12 o’clock at night; blowed on Tuesday morning, 20th, about 6 o’clock; made the first casting on Wednesday the 21st, about 7 o’clock in the evening; the average amount of Pig Iron per week was 18 tons." But Mr. Backhouse, although his business transactions were characterized by thoroughness and precision, had nevertheless been injudicious in purchasing Durham from the commissioner of confiscated estates. The legal proceedings instituted against him in 1791 resulted unfavorably to his interests two years later, and although the action of the state authorities in conveying the property to him was then set aside, it does not appear that he was ever reimbursed, save in the miserable pittance of four hundred and fifteen dollars appropriated by the legislature in 1808 for expenses incurred in defending his title. But with his nominal possession and active management the active operation of the works also ceased in 1791. Immense piles of bomb-shells and solid shot were removed from the premises in 1806, and the deserted buildings were then allowed to decay, having outlived several generations of those who had been sheltered in their daily toil by their walls. The furnace was not then suffered to die a natural death (if it may be thus personified); it was removed in 1819, when the grist-mill that marks its site was erected. A stone having date "1727" was preserved from the accumulated rubbish, and was an object of interest at the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876; it now occupies a conspicuous corner in the office of the iron-works. Adolphus William Desart Burton disposed of the property in 1847 at public sale, consisting of eight hundred and ninety-four acres divided into several farms, to Joseph Whitaker & Co. Deed dated March 16, 1848, when possession was given for fifty thousand dollars. They built two new furnaces adapted for the use of anthracite fuel on the site of the present one in 1848—50, and thus, after the lapse of more than one-half a century, the sounds of peaceful industry were again echoed and re-echoed from the Durham hills. Hon. Edward Cooper (son of Peter Cooper), and Hon. Abram S. Hewitt, of New York city, purchased the works from Joseph Whitaker & Co., in 1864, for one hundred and fifty thousand dollars, but disposed of them the following year to Lewis Lillie & Son of Troy, New York. The plant was enlarged and improved by the latter and adapted to the manufacture of Lillie’s chilled iron safes on an extensive scale. Failing to meet their obligations to Messrs. Cooper & Hewitt, the property reverted to the latter in 1870, and the manufacture of safes was then abandoned; they continued, however, to operate the two blast furnaces until 1874, when they were demolished and the erection of one large furnace commenced which was first put in blast February 21, 1876. The two furnaces erected in 1848 and 1850 were 40 feet high. One was 13 feet and the other 14 feet in diameter. They were afterward enlarged to 48 and 50 feet high by 15 and 16 feet internal diameter respectively; they were built of stone and lined with fire-bricks in the usual way, had open tops, and were equipped with iron pipe stoves or ovens for heating the blast. It is estimated that the entire output of these two furnaces from the time of their erection was 178,000 gross tons of pig-iron, with an average weekly output during the actual time in blast of 100 gross tons for each furnace. It required about two tons coal, two tons three cwt. of ore, and seventeen cwt. of limestone to produce one ton of pig-iron. The total stock consumed by these furnaces can therefore be estimated as follows:- 356,000 tons coal, 382,700 " ore, 151,300 " limestone. Coal was brought to Durham on boats from Mauch Chunk through the Lehigh and Delaware Division canals; the limestone was quarried from the property. The ore mixture contained about sixty per cent. of primitive ore from the Durham mines and forty per cent. of brown hematite, part of which was also mined from the Durham furnace tract and the balance from other mines in the neighborhood of Durham. The present furnace, completed in 1876, is 19 feet diameter or bosh by 75 feet high. It is built of sheet-iron supported by heavy cast-iron columns. It has a closed top and is equipped with six hot-blast ovens which were designed by Hon. Edward Cooper. This particular form of oven, first in use at these works, is very economical, and has been adopted by many other furnaces throughout the country. Blast is supplied by two upright blowing engines of 4 feet stroke with 44 inch steam cylinders and 84-inch blowing cylinders. Each engine therefore blows 308 cubic feet of air per revolution.** In the present practice they are run to their capacity, 30 revolutions, and deliver 18,472 cubic feet of air per minute. The boilers are of the ordinary cylindrical type of furnace-boilers, 24 in number, 12 steam-boilers 36 inches diameter by 60 feet long, and 12 mud-boilers 30 inches diameter by 40 feet long. The plant further consists of pump-house, foundry, and machine shops, blacksmith shops, wood-working shops, saddler shop, office, laboratory, and other necessary buildings. The employees number 350 men and boys. Some of the men employed in the erection of the furnace in 1848 have worked continuously here ever since. The present furnace was put in blast February 21, 1876, and up to February, 1882, divided into four blasts, produced 99,992 1/2 gross tons of pig-iron, being a weekly average of 388 tons during the actual time in blast. The fifth blast, lasting 151 weeks, commenced April 1, 1882, and produced 90,450 gross tons, or a weekly average of nearly 600 tons. The sixth blast commenced July 1, 1885, and up to July 1, 1887, had produced 66,779 gross tons, or a weekly average of over 642 tons. At present writing the furnace is still running successfully in her sixth blast. The coal required during the fifth and sixth blasts is a little less than 1 ton 4 cwt. per ton of pig-iron. The output in one month has reached 3,135 tons, in one week 752 tons, in one day 129 tons, while the lowest weekly fuel consumption is one ton per ton of pig-iron. Since 1876 the Durham mines have produced about 34 per cent. of the ores used in the mixture. 11 per cent. was brown hematite from Durham and Springfield townships, and from Williams township, Northampton Co. The remaining 55 per cent. of the mixture was from properties belonging to Messrs. Cooper and Hewitt, situated in Morris and Passaic counties, New Jersey; but when making iron suitable for Bessemer steel large quantities of ore are imported from Elba, Spain, Africa, and many Mediterranean ports. To bring this ore and other material necessary to supply a plant with the increased production, it was found necessary in 1876 to build a ferry across the Delaware in order to get connection with the Belvidere Division of the Pennsylvania railroad; tracks were put down on both sides of the river and the cars carried over into the works without transferring; the ferry-boat, 20 feet wide by 80 feet long, is operated in the usual old-fashioned way by the current of the stream, and a stationary wire-cable. The cars are run on the boat over an iron truss bridge 30 feet long, which is lifted from and lowered on the boat by cranes erected for that purpose, one end being hinged to the dock, thus making a continuous track. It requires two locomotives to deliver the cars to and from the boat, one on each side of the river. The entire output of pig-iron is taken across and shipped in this way. When the river is in favorable condition the capacity of the ferry is about 500 tons daily, or 250 tons in each direction. No small part of the operation of a blast furnace is the handling of the slag or cinder. At Durham this amounts to 100 tons every 24 hours. It is run into cast-iron cars and carried away over a narrow-gauge track by means of a narrow-gauge locomotive. All the available space around the furnace and around the river front having been filled, the present dump is on the northeast end of Rattlesnake hill. As we have already shown, the mining of ore probably commenced as early as 1698, and that in 1727 ore was regularly mined to supply the blast furnaces which continued in operation with the usual interruptions until 1791; it is probable that the ore mined from the Durham hills during this time aggregated 150,000 tons. The entire quantity furnished by the Durham mines up to the present time would therefore approximate 550,000. This, however, does not include the brown hematite mined from the furnace tract or from other properties in Durham. The ore from the Durham hills is primitive and not magnetic; it is found on two hills, one called "Rattlesnake," situated nearest the furnace and about 1500 yards from the Delaware river, the other, called "Mine hill," situated further to the west, extending beyond but south of the village of Durham where the original furnace was located. The mining operations of 1727—1791 were evidently confined to "Mine hill." In 1846 this entire hill was leased to the Glendon Iron Company, which worked it in connection with their adjoining tract. Their lease expired in 1848, when Joseph Whitaker & Co. took possession; when the mine was reopened after having been idle for more than fifty years, some of the timbers were sound and some old tools were found. This opening was known as "old tunnel;" it started on the western end of the hill running northeast, and was the principal source of ore supply for some years; a shaft was put down intersecting this "old tunnel," and the ore worked out at a depth of 250 feet, being 70 feet below the level of the old tunnel. The Glendon Iron Company continued to work their own mines (shipping the ore by canal to their furnaces at Glendon, Pa.) until 1857, when they abandoned them; in 1875 their property on Mine hill known as the "Glendon lot" was purchased by Messrs. Cooper and Hewitt, and thus again became part of the Durham furnace tract. In 1859 a tunnel was commenced on the north side of Mine hill, near the Creek level, running southwest. This is known as the "new tunnel," and was intended not only to drain the "old tunnel mines," and make the expensive machinery for pumping and hoisting no longer necessary, but also to cut the shoot of ore at a greater depth; and further to fully test the ground on the north side of the hill several small shoots of ore were intersected, but they were not large enough to justify working. Work was not carried on regularly, and it was not until 1874 that the old workings were reached, the new tunnel having attained a length of 2000 feet. Since then drifts have been run in every direction, and considerable ore mined. In 1858 an opening was first made on the south end of Mine hill, the ore outcropped on the surface, and the mine was therefore called "surface mine." Work at this point was suspended in 1862, and resumed in the fall of 1878, when a slope or inclined plane 200 feet long was sunk. This led to the discovery of a new shoot of ore, which was 30 feet wide at the largest place, and richer in iron than the old surface ore. The shoot was 500 feet long, and had a maximum height of 40 feet. There are two other shoots of ore at this place, one 75 feet to the south, which was 300 feet long and at places 12 feet wide. The other shoot is 100 feet to the north, outcropping at the surface, has a maximum width of 18 feet, and is 350 feet long. Since reopening this mine in 1878, it has been the principal source of supply from the Durham hills. There are several other openings on this hill, from which small quantities of ore are mined. Operations on Rattlesnake hill commenced in 1851 on top and near the center of the hill. The ore outcropped and was worked as an open cut. In 1853 a tunnel was commenced on the north side of the hill near this open cut some 200 feet above the Creek level. At this place two "veins" of ore were intersected, the first one called "Rattlesnake vein," the other overlying vein called "Back or South vein." The general strike of the ore is northeast and southwest, pitching southeast and dipping south. A slope from the end of the tunnel was put down on the "Rattlesnake vein," following the dip of the ore. At intervals of 50 and 100 feet levels were made and the ore stopped out. At present there are five levels, and the slope or incline is 350 feet long. In 1854 a tunnel, called "hollow tunnel," was put into the eastern end of the hill, about eight feet above the Creek level, and a larger quantity of ore produced at a cost of 90 cents per ton delivered at the furnace. The pocket of ore having been worked out, this tunnel was abandoned in 1862, but in the fall of 1878 operations at this point were resumed by the driving of another tunnel about 75 feet farther to the south. This is also called "hollow tunnel." After drifting some 500 feet the "Back or South vein" was intersected, and the vein followed on its course some 500 feet more. The ore varies in thickness from six inches to ten feet. A cross-cut running north was then started at a point 500 feet from the mouth of the tunnel (where the "Back vein" was first cut), and after drifting 175 feet the "Rattlesnake vein" was intersected, and the tunnel of 1854—1862 explored; it was found to be five feet lower than the present "Hollow tunnel," and running on the course of "Rattlesnake vein." This course was then followed, and work pushed vigorously to connect with Rattlesnake mine. At the same time the lower level in Rattlesnake mine was continued going east. The connection was made September 8, 1885, at a point about 500 feet from where the vein was first intersected, being 1000 feet from the mouth of the "Hollow tunnel." The drift in the bottom of Rattlesnake mine was 500 feet from the slope where the connection was made, and was 50 feet above the hollow tunnel. At the point where the connection was made the vein is 12 feet thick, and the ore richer in iron than any other ore on the Durham property. The Rattlesnake vein varies in width from two feet to 50 feet, with an average width of ten feet. There are several openings in Back or South vein on the eastern end of the hill, which consists of shafts, small tunnels, and open cuts. In 1872 considerable ore was mined under contract from one of the surface openings. The principal brown hematite opening on the Durham tract, or in Durham township, was the "Orchard mine," on the northeastern end of Rattlesnake hill, 800 feet north of the Hollow tunnel. Operations here commenced as early as 1849, and continued for some years until the mine was exhausted. In 1876 the mine was re-opened, but no appreciable quantity of ore taken out. The primitive ore from the Durham hills is quite low in phosphorus and sulphur, and contains no other objectionable impurities. Comparatively speaking, they are not rich in iron, but are admirably adapted to mix with other ores, and produce a mill iron of unusual strength. They are also suitable chemically for making pig-iron for Bessemer steel, and are at present being used largely in the mixture for that purpose. Analyses of the Durham ores are shown by the following table:— Settlement in Durham followed the discovery and development of its mineral resources. Europeans were living within the limits of this township as early as 1723, and their settlement was the outpost of civilization along the Delaware at that time. It seems probable that immigration thither began some years earlier, but of this there is no conclusive evidence. The English element predominated for some years, and until farming began to receive some attention. While the first settlers arrived by way of the Delaware, the Germans who followed reached Durham valley through Springfield and from Williams and Allen townships on the north. And thus, while the agricultural pursuits of the township are almost exclusively in the hands of persons of Teutonic descent, the population at the furnace has always been made up mostly of English, Scotch, and Irish. It does not appear that the corporate ownership of the land encouraged immigration; and hence it was not until after the partition of 1773 that the population had increased sufficiently to warrant the erection of this township. Efforts had been made much earlier than this, however, and it seems probable that the Durham tract was recognized as a municipal division long before its organization as such. Constables and justices of the peace for this section were appointed by the court as early as 1788. The agitation for local government culminated in the northern part of Bucks county in 1743, when Springfield was erected, and like action may have been taken with regard to Durham but for the conflicting wishes of its people, some of whom desired to be annexed to it, while others, including the furnace proprietors, petitioned for separate municipal privileges. June 13, 1775, a petition with this latter end in view, signed by Jacob Clymer, Henry Houpt, George Taylor, George Hemline, Wendell Shank, Thomas Craig, Michael Deemer, William Abbott, and others, was presented to the court, and the importunity of the agitators was at length successful. Durham township was erected with metes and bounds identical with its present limits and an area of five thousand seven hundred and nineteen acres. It is the smallest township in the county with a single exception, but one of the most important in wealth and resources. The roads first opened in Durham were characterized by a general convergence toward the furnace. The "Durham road," one of the principal thoroughfares of the county, was so named from the northern terminus, toward which it was slowly completed for nearly three-quarters of a century. It was begun in 1693 and completed from Bristol to Newtown. With successive additions at irregular intervals, it was extended to Durham in 1745 and to Easton ten years later. Roads had also been opened westward to intersect the Bethlehem road prior to 1755. In 1767, the court was petitioned to disregard applications for any more roads, as there were enough already. The river continued to be a most important highway. Durham boats were quite as well known as Durham stoves. These boats were about twenty feet in length, and manned by five men, one of whom was at the helm, while two with stout poles in their hands stood at each side and propelled the craft by pushing against the bottom of the stream. When moving against the current, it was possible to progress at the rate of twenty-five miles a day. It is said that the first boats were built on the river bank, near the cave, by one Robert Durham, from whom the name was derived. They were found to be remarkably well adapted to river navigation, and were extensively used until canals rendered them unnecessary. In every part of the world and at every period in its history, population has concentrated under well-defined laws, to which Durham has not been any exception. Its villages, Durham, Monroe, and Riegelsville, have become such because of the advantages of their geographical situation, the energy and persistence of their founders, or the industrial enterprises which attend and sustain their population. Riegelsville may be said to combine these conditions of healthful expansion. It is the most northern village in the county, twenty miles from Doylestown, and ten from Easton, situated upon an alluvial deposit, which was formerly an island in the Delaware river. At a period anterior to its settlement by Europeans, it was the site of an Indian village known as Pechoqueolin. Upon the partition of the furnace lands in 1773, it was included in tracts numbers 32 and 33. The latter embraced one hundred and ninety-three and one-half acres, and became the property of Joseph Galloway, from whom it passed successively to Joseph Morris, Thomas Long, Michael Boyer, Abraham Edinger, Jacob Uhler, John Leidy, and Benjamin Riegel. Plot number 32, south of the main street of the town, came into possession of James Hamilton, who disposed of it to Wendell Shank in 1774. Either through improvidence or because of unfavorable surroundings the Shanks suffered greatly during the first years of their residence here. It is related that they were compelled to feed the thatched roof of the barn to famishing cattle during two consecutive winters. Their house was situated near the river bank, upon the site of Abraham Boyer’s residence. They were the first proprietors of the Riegelsville ferry. The only neighbor near enough to be called such was Jacob Moser, who kept a cake and beer shop for the accommodation of ferry hands. Three Shank brothers lived at the ferry which bore their name. Practically the growth of the town began in 1814, when Benjamin Riegel (farmer) erected the large stone barn still standing. The stone house was built in 1820; and in 1830 Benjamin Riegel (miller) located upon the plot number 33, which he had purchased from John Leidy the same year. In 1832 he erected a brick mansion occupied at this time by Mr. W.F. Adams. About this time he first began to see the advantages of the place as the location for a town; and on the 15th day of January, 1834, by his direction, Michael Fackenthall surveyed twenty-four building lots, twelve of which fronted on the canal, and an equal number on the Easton road. Among the first purchasers of these lots were W.H. Townsend, Thomas Brotzman, Daniel Landa, and Benjamin Walters. The opening of the canal in 1832 gave an impetus to mercantile and industrial pursuits. The first store was opened in the year previous (1831) by Messrs. Jesse Heany and Jacob Leaver, and a second in 1832 by Messrs. Heany and Riegel. In 1831 the village comprised this first store, a tavern, and these dwellings. The tavern was kept by Benjamin Riegel (farmer), who applied for license soon after completing his commodious dwelling in 1820. He erected the large hotel building at the river bridge in 1837 or 1838. Isaac H. Bush was landlord here from 1841 to 1848. John Dickson was proprietor from 1851 to 1868, David Walters from 1868 to 1871, and Joseph Rensimer from 1871 to the present time. In 1841 Tobias Worman removed from Tinicum and engaged in merchandising here, and in 1845 he was appointed first postmaster by President Polk. He was succeeded in 1848 by Benjamin Riegel, but the latter retained him as deputy, so that the change was merely nominal. Mr. Worman continued as the incumbent of the office until 1859, a period of twenty-four years. Frederick M. Crouse succeeded him in that year, but was removed in favor of G.W. Fackenthall under the present national administration. Riegelsville became a money-order office in 1879. Prior to 1869 there was but one daily mail; but about that time a tri-weekly service was established between Quakertown and Riegelsville, which, in 1878, was merged into a daily mail. There are also direct overland mail communications with Doylestown, and numerous daily arrivals of mails from points on the Belvidere Delaware railroad. The Riegelsville post-office has always been in honest, capable, and energetic management, and in an existence of forty-two years has become the most important post-village in this section of the county. Besides numerous local roads (the first of which was opened in 1815 or 1816) and the canal, the village is connected with Riegelsville, New Jersey, on the Belvidere Delaware railroad, by a substantial wooden bridge, and enjoys many advantages from that line of traffic. The ferry flats had long been inadequate for the constant stream of travel before the project of building a bridge assumed tangible form. A company was formed in l837 with Hon. William Long president, and Benjamin Riegel secretary. The structure first erected was swept away in the great freshet of January 8, 1841, and the present one erected. In 1850 Riegelsville comprised one store, one tavern, and eleven dwellings. A draft of the village in that year locates the residences of Benjamin Riegel, farmer; Benjamin Riegel, miller; Anna Bush, John Clymer, C.W. Fancher, Tobias Worman, Samuel Dilgard, John Boyer, Hannah Riegel, Peter Uhler, and William B. Smith. The site of Clark & Cooley’s hardware store was then occupied and for a long time previously by a limekiln. The building area was greatly increased in 1877 by the sale of several tiers of lots south and west of the town from land formerly owned by Mr. Abraham Boyer. The present population approximates five hundred. The principal industrial establishment is the carriage manufactory of Mr. W.P. Helms, which has been in successful operation since 1875. Religious and educational interests are well represented. A number of secret and benevolent societies are also sustained. Peace and Union Lodge, No. 456, independent Order of Odd Fellows, was instituted September 11, 1851, with Michael Uhler, N.G.; Christian Hager, V.G.; Christopher Wykoff, secretary; Samuel Dilgard, assistant secretary; and Smith Clark, treasurer. A large hall built in 1861 belongs to this association. Colonel Samuel Croasdale Post, No. 256, Grand Army of the Republic, was organized June 14, 1882, with the following members: Frederick Crouse, Solomon Wolfinger, L. Quintus Stout, G.W. Fackenthall, Andrew J. Crouse, Samuel Shaffer, William W. Clark, Edward Renseimer, Jacob E. Saylor, Robert Brodt, M.S. Maguire, Henry Warford, C.E. Hager, John Y. Bougher, Joseph Leister, Aaron Miller, Isaac M. Smith, Edward Deemer, Jeremiah Transue, Christian Bratzman, Adam Bigley, William H. Crouse, Franklin Lehr, William Marsteller, William S. Mettler, William Taylor, and S.D. Bigley. Among the other valued contributions to the Post is a portrait of Colonel Croasdale, executed by Miss Elizabeth Croasdale, his sister, and a former superintendent of the Philadelphia School of Design. Fraternal Council, No. 158, Order of United American Mechanics, was chartered April 26th, 1858. First officers were John J. Campbell, Solomon Wolfinger, Michael Wolfinger, and Samuel Dilgard. A fine hall valued at three thousand dollars is owned by this association. Prosperity Loge, No. 567, Free and Accepted Masons, was instituted September 4, 1886, with Edward W. Lerch, W.M.; Dr. Alexander S. Jordan, S.W.; Dr. Newton S. Rice, J.W.; and nine other charter members. The warrant for its organization was granted July 16, 1886. The village of Monroe is situated at the mouth of Rodger’s run, about two miles below Riegelsville, and is embraced within the boundaries of plot No. 13 of the Durham lands. This embraced one hundred and seventy-six acres, and came into the possession of Thomas Purcell some time prior to 1780. He first erected a log-cabin; then a saw-mill, the first in this region, and afterward excavated a large mill-pond, and also built a second mill. He established a ferry in 1785, which at once became an important thoroughfare from Sussex, in Jersey, to Philadelphia. He opened a road from the ferry to the Durham road by way of Gallows run, and thus increased the patronage of his mills. He was a man of invincible energy and remarkable sagacity. He died at Musconetcong, New Jersey, and is buried in a deserted graveyard near that place. The Monroe post-office was opened in 1832 with John H. Johnson as postmaster, which position he held twenty-six consecutive years. In May, 1858, William Bennett was appointed, and in June, 1866, Matthias Lehman superseded him. In 1841, however, the name of the office had been changed to Durham, and in 1869 it was discontinued at Monroe, and removed to the store at Durham iron-works, and in 1876 (Feb. 5) it was removed to Bachman’s store with Hon. R.K. Bachman as postmaster, where it still remains. Durham village is about equidistant from the Springfield and Nockamixon boundaries. It comprises the grist-mill of R.K. Bachman & Bro., store, post-office, and about ten dwellings. Postal facilities to this place have had a checkered history. It is said that the furnace managers established a mail service at an early date. Richard Backhouse was the first proprietor who reduced this to a system, and about the time of his death (1792) the first United States postal law was passed. James Backhouse, 1798—1805; George Heft, 1805—1813; Dennis Reilly, 1813—1818; Nathan Reilly, 1818—1825; Thomas Long, 1825—1836, were successively landlord or storekeeper, and as such post-master. The office was discontinued in 1836, and in 1876 the Monroe post-office was removed to Durham, when R.K. Bachman became postmaster as above described. He was nominated for congress several years afterward, and Edward Lerch succeeded him. Durham schools compare favorably with those in other sections of the county. The first school-house in this section of the county was the "Old Durham Furnace school," built in 1727. It was a small log-house on the east side of the road leading from Easton to Philadelphia, about one hundred yards north from Durham creek. The only teachers of whom any record exists were James Backhouse, whose proficiency in mathematics was extraordinary; John Ross, subsequently a judge of the supreme court of Pennsylvania; Thomas McKeen, afterward president of the Easton National Bank; and Richard H. Horner, who taught in 1784 at a salary of seven shillings sixpence per day. The singing school was an important adjunct under his administration. This school-house, the educational pioneer of northeastern Bucks county, was demolished in 1792. The Laubach school has probably influenced the farming community more than any other in the township. Among the teachers here were Jacob Lewis in 1813; Dr. Drake, a man of great scientific acquirements, in 1815; Michael Fackenthall, a proficient surveyor, in 1817; James Rittenhouse, a relative of the great mathematician, in 1822; and Mr. Stryker, a rigid disciplinarian, in 1833. The first school-house in the Rufe district was of logs, built in 1802. The ground necessary for its erection was donated by Samuel Eichline. In 1861 the old house was burned and the present stone building erected. Among those who have taught here were Dr. Joseph Thomas and Hon. C.E. Hindenach. The new Furnace school-house was built about 1855, and destroyed by fire in 1876. A graded school built on land donated by Cooper & Hewitt was opened in February, 1877, with N.S. Rice principal, and C.W. Fancher assistant. The McKean Long school-house, a typical structure of the olden time, was built in 1802 to accommodate those families who were not convenient to Rufe’s or Laubach’s. It is a long, low, stone building and many of the older residents of the township point to it with just pride as the place where the foundation of their future usefulness was laid. The first school-house in the Monroe district, a small frame building, was erected in 1838 upon ground donated by George Trauger. The more pretentious structure in use at the present was built in 1865. Among those who have taught here were Dr. S.S. Bachman, John Black, Reverends L.C. Sheip and C.H. Melchor, Dr. B.N. Bethel, Dr. C.D. Fretz, and D.R. Williamson. The Durham Church school-house was built in 1844 upon ground donated by John Knecht, Sr. Jacob Nickum was the first teacher; Aaron S. Christine and Carrie Fackenthall were among his successors. The present school-house is a commodious building, and compares favorably with any other in the county. The first school-house in Riegelsville was built in 1846 and opened with Dr. R. Kressler as teacher. G.F. Hess, H.H. Hough, Rebecca Smith, and David W. Hess were among its teachers. August 3, 1857, C.W. Fancher opened an academy in the Presbyterian church. D.R. Williamson took charge September 1, 1869; Dr. George N. Best, September 13, 1871; John Frace, September 30, 1872; but for want of support the project was abandoned. After a suspension of ten years the effort to establish a school of advanced standing was renewed. Through the efforts of John L. Riegel, Esq., Professor B.F. Sandt, a former student of Lafayette college, was induced to open an academy. It has outgrown the accommodations at first provided, and since September 3, 1886, has been conducted in a large stone building erected mainly through the munificence of Mr. John L. Riegel and deeded in trust for educational purposes to the trustees of St. John’s Reformed church in the United States. A circulating library is one of its most valuable features. The institution reflects credit upon its projectors and cannot fail to exert a favorable influence upon the social and intellectual life of the community. The earliest account of any religious services being held in this township places it in 1728 at the school-house connected with the iron-works. The Presbytery of New Brunswick sent supplies to Durham in 1721. The Durham Presbyterian congregation was fully organized in 1742, and supplied from different Presbyteries, principally the one above mentioned. There was a considerable influx of Germans from Easton, and in 1790 a German Presbyterian congregation was organized and services held in a log barn belonging to George Henry Knight, about five hundred yards west from Durham church. Reverend John Jacob Hoffmeyer preached here in 1794 to 1806. German services were also held in the log school-house, popularly known as Laubach’s by preachers from Easton. The religious complexion of those who worshipped at this latter place was principally Reformed and Lutheran. In 1812 these three congregations united in purchasing land from William Long, and appointed John Jacoby, Michael Zearfoos, Morgan Long, Anthony Trauso, John Boyer, Jacob Uhler, and Jesse Cawley trustees for the erection of a church building, which was completed in 1813. The altar was three feet high and three feet square, surrounded by a railing of equal height, twelve feet square. The deacons passed long poles with black velvet bags at the ends to receive contributions. There were three doorways, and an equal number of stairways ascending into the galleries. This church is said to have been exceedingly uncomfortable in cold weather. It was replaced in 1857-58 by the Durham Union church of the present, one of the most beautiful edifices in the county. From a distance only the white spire is visible above the surrounding trees. The following Presbyterian pastors have officiated here: Stephen Boyer, Bishop John Gray, Joseph McCool, 1833; Joseph Worrel, 1836; John W. Yeomans, D.D., 1843; Charles Nassau, D.D., 1844; John Carrol, 1849—53; William C. Cattell, D.D., LL.D., 1856—60; John L. Grant, 1860—65; and G.W. Achenhaugh, D.D., 1866—67. The numerical strength of the Presbyterian congregation has declined steadily since 1843. A Presbyterian church was built at Riegelsville in 1849. This was subsequently sold by order of the county court, and the congregation disbanded. And thus, after a checkered experience of one hundred and thirty years, all efforts to maintain Presbyterian services in Durham have finally been relinquished. The first German Reformed pastor was Reverend Samuel Stahr, who preached at the Union church from 1812 to his death in 1843, when he was buried in the graveyard adjoining. He was succeeded the following year by Reverend W.T. Gerhard, who introduced English preaching. The present pastor, Reverend D. Rothrock, succeeded him in 1859. The first Lutheran pastor was Reverend John Nicholas Mensch, who preached from 1811 to 1823, and was succeeded by the following: 1823—1838, Henry S. Miller; 1838—1842, C.F. Welden; 1842—65, C.P. Miller; 1865—79, W.S. Emery; 1879, O.H. Melchor. Upon his accession the congregation severed its connection with the Ministerium of Pennsylvania, and united with the general synod of the Lutheran church. The Lutheran church of Riegelsville was organized in 1850 by Reverend John McCron, D.D., then pastor at St. James’ church, near Phillipsburg, N.J. His pastorate continued but a few months. Rev. J.R. Wilcox was pastor from 1851 to 1860; Rev. C.L. Keedy, in 1862; Rev. Nathan Yeager, in 1863; Rev. Theophilus Heilig, in 1864—76; and Rev. D.T. Koser, 1877 to 1887; Rev. C.L. Hech is the present pastor. The church building was erected as a Union house of worship in 1851. Believing that the only ground upon which the divided state of the Christian church can be justified is that each denomination has its peculiar and individual work, an amicable division of this property was effected in 1871, by which the Lutherans became its exclusive owners. July 7, 1872, the corner-stone of a new Reformed church was laid with impressive ceremonies. The church is substantially built of brown stone, and is beautifully frescoed. This congregation was organized by Reverend John H.A. Bomberger, D.D., LL.D., December 21, 1851. Dr. Bomberger was then pastor at Easton. He was succeeded in 1854 by Reverend Thomas G. Apple, D.D., LL.D.; in 1856, by Rev. William Phillips; in 1862, by Rev. George W. Achenbaugh, D.D., LL.D.; in 1873, by Rev. R. Leighton Gerhart; in 1879, by Rev J. Calvin Leinbach; and Rev. B.B. Ferer, the present incumbent, preached here for the first time, October 31, 1884. The membership now numbers 250, and owns much valuable and substantial church property as before mentioned. It holds in trust the academy building and teachers’ residence for educational purposes, besides possessing a commodious stone parsonage and a comfortable sexton’s house. The congregation has also received an endowment of $5000, which is to draw perpetually an annual interest of six per cent. from Mr. John L. Riegel. It is also a fact worthy of note that three of these Reformed pastors subsequently became college presidents, and two of the Lutheran pastors became principals of leading ladies’ seminaries in the country. The Roman Catholic persuasion has been represented by its membership from an indefinite period, but no public religious service was held until 1849, when Father Reardon, of Easton, celebrated mass in private houses. He was the first priest to officiate at Durham. The following clergymen have succeeded him: Wachter, Newfield, Koppernagel, Laughran, Marsterstech, Stommel, Walsh, and Krake. A chapel was erected in 1872 near the furnace on property donated by the furnace company, during Reverend Stommel’s incumbency. Methodist Episcopal services were held in houses along the Rattlesnake as early as 1850, but it was not until 1865 that a degree of regularity was observed. Reverend Robert C. Wood was pastor during part of this time. When the new building for a graded school in the Furnace district was built in 1872, one of the old school-houses comparatively new was purchased by the congregation, and after undergoing alterations it was dedicated as a place of worship, J. Bowden being pastor at that time. Services have been conducted regularly since then. The original Methodist population was small, but it has been increased in recent years by the arrival of English people, mostly miners from Cornwall, of that denomination. The society is in a flourishing condition.

* This case, Jenks vs. Backhouse’s Heirs, is reported in 1 Binney, 97; it was argued in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in June, 1798, and again December 7, 1798, and was decided December 23, 1799. ** This could be compared to the blowing machines used at the old furnaces, 1727-1791, when bellows operated by water-power were used. |

||

| Page last updated:Monday July 07, 2008 | ||

|

If

you have a homepage, know of a link or have information you wish

to share. or would like to volunteer to transcribe information

for the Bucks Co. PA please email: |