Book Cover

Photo courtesy of Mike Clarke

Book Cover

Photo courtesy of Mike Clarke

Sullivan County Industries--Then and Now Published by The Endicott Printing Company, Endicott, NY |

Acknowledgement

The following named, present and former residents of our home land, have contributed data or manuscripts to this chapter of Sullivan County’s eventful history

Mrs. Myrtle Magargle, Maurice J. Harrington, A. F. Snider, T. O. McCracken, B. T. Martin, Frank Cox, Ralph King, Otto Little, Nelson C. Mullen, Mrs. L. L. Baumonk, Mrs. Emma Hesse, Mrs. Elizabeth Angle, H. W. Bender, Miss Jessie Wreed, Hon. Walter Baumonk, Roscoe Burgis, Wm. Monahan, Mr. And Mrs. Arthur Miner, James Bowles, Frank Bedinsky, Jr., Pete Kratcoski, Jr., Fred Rogers.

The Aim

The purpose of these recorded facts, gleaned from records and remembered experience of contributors, is to bring to promoters and toilers in local industry appreciation and thanks for their efforts in contributing to the welfare of their fellow citizens by creating the necessary commodities, the sale of which provided wages for the toiler and, in turn, became the life blood of business, professions, churches, schools, liberal arts and crafts, created markets for the produce of agriculture and sustained every human effort for community betterment.

Paying tribute to local brain and brawn in cooperative industry, we honor America’s strength and the last best hope for world freedom. The useful lives of these community benefactors issue a challenge to future generations to produce, under more favorable circumstances, better products and improved opportunities for our fellow men and women, irrespective of race, creed or national origin.

Frontispiece

Photo courtesy of Mike ClarkeSULLIVAN’S INDUSTRIES -- THEN AND NOW

Human existence has always depended on the untied efforts of the human family. In prehistoric days, man learned that cooperation was the cornerstone of the foundation upon which his superstructure of civilization rested; be it slave or free. If today we are to make our discoveries and inventions of benefit to the world, we must learn the art of working together, as well as living without dissentions. First of all, we start with our neighbors, giving them the right to exchange their products with us and with others in the same proportion of use and beauty that we expect for ourselves.

The dawning of the nineteenth century found homemakers supplying the most of their needs for food and clothing, tools and equipment upon their own farms. But into community life there soon appeared the local carpenter, mason, wheelwright, blacksmith, weaver, tinker (handy repair man), peddler, the itinerant preacher, and the schoolmaster frequently versed in the art of music and dancing; the cobber, dressmaker, milliner, the self-taught lawyer, bone-setter, the herb doctor, the coffin maker who usually made furniture, and in every neighborhood at least one genius who could turn his hand to anything, usually making a success of nothing.

Apparently the first cooperative effort in Sullivan County was the building of roads, closely followed by use of natural resources. Settlers of the land went together into the forest and burned lime and charcoal, boiled potash, made maple sugar by boiling maple sap, cured hides and furs from the wild animals, and built primitive water mills to aid in the manufacture of lumber and in grinding the grain, from which the miller subtracted his toll.

Maple Syrup on Sale

This is a picture of the sugar house belonging to Dale Bennett of Estella. The Bennetts sold maple syrup for many years, and Linda Bosnak, our contributor, can remember visiting and seeing how the syrup was made.

Photo courtesy of Linda Bosnak, the litle girl in the picture.The year 1930 marked the passing of large scale industry, due to depletion of natural resources, including lumbering, tanning and mining, dealing a staggering blow to business and industry from which Sullivan County is now steadily recovering.

In 1895, our population numbered approximately 14,000, more than 5, 000 may have been wage earners in industry. Wages were considered normal by comparison with other localities where living cost were higher. Long hours and lack of machinery, plus company stores and other unfavorable conditions, lead men and women who remember these trying times to conclude that with fewer people employed, we of today are ahead both financially and in improved working conditions.

In 1950, the Pennsylvania Department of Internal Affairs reported 837 persons of legal age employed in twenty plants, with aggregate earnings totaling $1,692,2000.00. Capital invested in raw materials, machinery, and buildings amounted to $1,464,4000.00. The value of products was $4,850,7000.00.

Average labor today, earns more in two hours than was paid for full ten-hour day at the turn of the century. In many instances the worker earns more in one day than was paid per month on farms by the very few farmers employing hired labor. They worked them from daylight to dark at a monthly wage of from $6.00 to $12.00; board and sleeping quarters found.

In fact, pioneer land owners bred labor on their farms, practically holding sons and daughters in bondage until they were twenty-one years of age.

These conditions, as experienced by today’s grandparents, may give a clearer understanding of the `good old days’ of fond memory as compared with the `better days’ as of now.

The Glass Factory

The first industry in what is now Sullivan County was a glass factory located at Lewis Lake, now called Eagles Mere. It was built and operated by an Englishman, George Lewis, whose business brought him to New York, where he met Joseph Priestly, Jr. Priestly was interested in the sale of thousands of acres of Central Pennsylvania land that was owned by the his family. His glowing description of the mountain forest induced Lewis to buy 30,000 acres.

In 1880, he had the tract surveyed, and two years later he spent six weeks near the crystal water he named Lewis Lake. During this time, yellow fever raged in the city and he felt he owed his life to this time he spent on the mountain. Later, recalling the pure white sand of the beach it seemed to him an ideal place for making glass. He decided to do that, and to make his home there.

By 1808, he built not only the glass factory, but also a grist mill, dwelling for his workmen, a store, and his own residence. The factory was located on Mount Lewis, now the site of the McCormick and Young cottages, at the southeast corner of Laporte and Eagles Mere Avenues. Sand was hauled from the upper end of the lake by flat boats, and one old resident says that it was also dredged from the lower end of the lake and brought out by six-horse teams.

Stones from the ruins of this old factory have been used in the foundation of the Presbyterian Church and in cellar walls of a number of houses in the borough. Moreover, one of the old mill stones is found today in the Episcopal Church, where it serves as a baptismal font. Relics of glass have been found in fragments of amber, blue, red and light green. There are a number of pieces of hollow ware still in existence, all privately owned. The few pieces remaining today are said by experts to be of excellent quality.

The glass was shipped from the lake to Muncy in hogsheads and was packed with straw from the Robert Taylor farm, eight miles away. From Muncy it was reshipped to Reading, Lancaster and Philadelphia. Conestoga wagons weighing 3,000 lbs and drawn by eight horses were used and, due to the very bad road conditions, there was always considerable breakage.

But the business flourished until after the second war with England. Glass was then imported and sold cheaper than Lewis could deliver it. Consequently, Lewis’ business failed. Then, too, his health was poor, so he returned to England in 1830, leaving his affairs and his unsold land in the hands of his brother-in-law. Soon after reaching England, he died. Because it had been his wish to be buried at the lakeside, his body was shipped back to New York. The month was August, and the heat intolerable; so it was found necessary to make interment in New York.

In 1831 the glass works was sold to John J. Adams, of Washington D. C. Meanwhile, the workmen had found employment elsewhere and most of them moved away. There is no record of the number of men employed.

The next account of the business appears in an advertisement, saying the stock had been bought by N. G. Lyon and Thomas Wells, and that they had leased the works for three months. Nothing more is known until the year 1838, when a nephew of Mr. Lewis came to the lake to settle up the property. The glass business had ended.

Ruins of an effort to manufacture glass was found near the ghost town of Thorne Dale and gave the name to Glass Creek. No records of legends of this small industry seem to have survived.

Woolen Mills of the Past

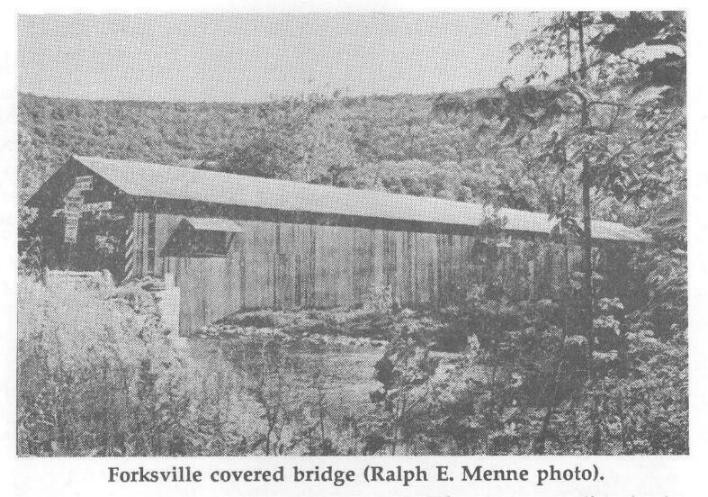

The Rogers Woolen Mill was built in 1810 near the abutment of the covered bridge at Forksville by Samuel Rogers. It may have employed ten men, and prospered during the war years (1812 to ‘14). The delivery of the finished product, blue Kernsey cloth for the U.S. service uniforms, required six weeks by Conestoga wagon. This plant was destroyed by a flood in 1816. A new mill was built two miles down the Sock in 1826, by Samuel and Jonathan Rogers and was sold the same year to John Ostler. This mill prospered during the was among the States and was operated intermittently until 1885. Obsolete spindles, a loom and carding machines were still in place when the old building was torn down in 1916. The only relic now left of this pioneer industry is an old dye kettle on the lawn of the Rogers home in Forksville. This kettle rolled nearly two miles down the Sock in the 1816 flood and for ten years rested in a deep hole, still known as the old dye kettle swimming hole. It was dragged from its muddy bed by oxen, for use in the second mill. Most of the flax and wool used was grown locally.

Flour Mills

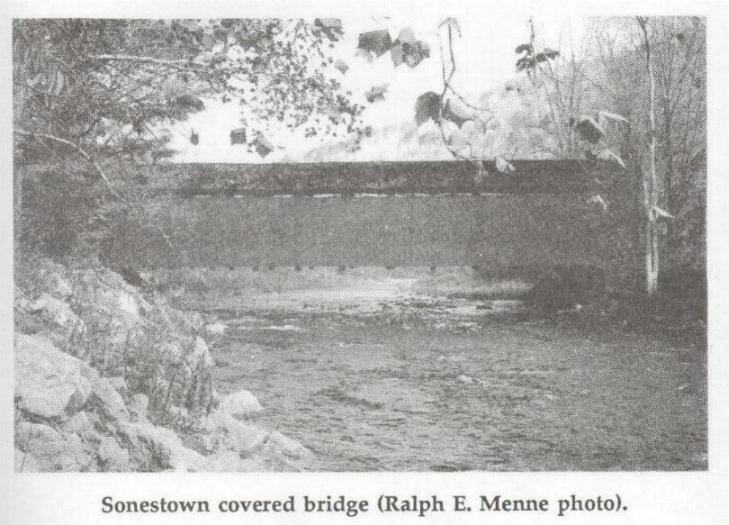

If making “burr” flour is to be included among the county’s early industries, the Hazen grist mill below Sonestown, deserves a prominent place. Its customers came from Laporte, Lewis Lake, Elk Lick, North Mountain and farms between. Its owner was John F. Hazen who built it about 1850. He operated it with the assistance of his son John N., who was better known as “Honse” (probably a diminutive for John from the German Johannes). After his father’s death Honse continued to operate the mill until around the turn of the century when it was sold to A. T. Armstrong and William Taylor, who installed modern machinery to make roller flour but closed down after a few years. The mill was razed to the ground a few years ago. Ruins of grist mills could be unearthed in every township.

Foundries

“Zack” Cole of Dushore, who is 88 years old, remembers the ruins of a water powered foundry at the top of Headley Avenue. Sections of the old dam still exist.

A second foundry in Dushore, now out of business, was owned by Monroe and Harry Bigger. Built in 1893, it was located near the high school. Old iron and junk was collected and sold there for twenty-five cents per 100 pounds. From this, castings were made into fly wheels, cast iron kettle, sap pans and many other articles.

As late as 1923, smaller foundries were built near the site of Harrington’s Creamery, and produced hand cultivators and farm machinery parts.

A Copper Mine

Streby’s History tells us that a copper mine was worked in Sullivan County near Beaver Dam, by a Boston capitalist about the time the county was separated from Lycoming, around 1849. It’s yield was too small to be profitable and operations ceased. It was again opened about 1900 by “Gus” Sones who had bought the Beaver Dam Hotel and adjacent land. This attempt also was a failure, although some zinc and silver were found, along with the copper, but not in sufficient quantity to justify production.

Cigar Factories

A cigar factory built during the nineties at Nordmont is almost forgotten. It was located here about the time the railroad extension to Laporte had sparked Nordmont into a second growth. James Deininger and his brother Al were the leaders in this little enterprise, which was short-lived when the building was burned by fire, along with the hotel next door. Probably a half dozen men or less were employed, the Deiningers from Hughesville and other local men. One-man cigar factories appeared at intervals in and around Dushore, making the good five cent cigar, listed by former Vice-President Garner as among our country’s needs.

Specht Brewery

The present price and restricted size of the glass of beer served over bars, causes old lovers of the amber brew to yearn for the days where for ten cents, one could have two quart growler filled, $1.25 would buy an eight gallon keg, and $1.00 would buy a case of twenty-four pints. On the backdrop for liquid drama would be painted the old Specht Brewery on Headley Avenue in Dushore, parts of which are now used as storage for a beer distributing plant.

In 1888, the ancient beer truck, drawn by mules, rumbled down to Forksville and Hillsgrove under cover of darkness and was met by young men, some of legal age, others under. The W.C.T.U. threatened dire punishment that failed to materialize, although Specht spent much time in jail for disturbing the peace. One aged resident of Dushore recalls that after moving to Ohio, brewer Specht figured in a domestic tragedy and murdered his wife. For this he was legally hanged, though the date and place of execution is forgotten.

Stone Whiskey Jug

Distributed by Francis M. Finan

Laporte, PA

See discussion of the local distillery industry below.

Photo courtesy of Nancy Spencer

Original auctioned on eBay in January 2015Schaad Distillery

Another liquid enterprise in the county, this one brought fame to Bernice for many years, was the Schaad Distillery. Very potent whiskey was distilled here and, in many cases, sold before it was sufficiently aged. Acquired by retailers in barrels and kegs; it found its way over bars in bottles bearing other brand names, thus aping the tale of the legendary stranger who produced every variety of wine from the same spigot of one cask during the Middle Ages.

Came the “noble experiment”, and the contents of the bond houses were taken over by the government. In some mysterious manner, better not remembered, it came into the possession of bootleggers and was dispensed; not altogether for medicinal purposes. This historic experiment is best summarized with the brief statement “gone but not forgotten,”

The following paragraph, clipped from the Review's “News and Views of 30 years Ago” may revive some memories.

Thursday afternoon county and state officers raided several places at Mildred and one at Laporte confiscating a large amount of wine, gin, whiskey, beer hard cider and moonshine. The largest haul was at Mildred where 49 barrels of Italian wine were found in one place. Sheriff Detrick deputized 10 men to dump the wine into the creek. Hundreds of spectators were on hand by that time and watched the wine run down the creek. Those raided posted bail for their appearance at March term of court.

Log Of Lumbering

Perhaps in some future age a musical genius will compose a symphony that will reproduce the chug of an old water wheel, the click of an up-and-down saw, the whine of a modern band saw, the deafening hum of a circle saw and the roar of a set of gang saws. The harmony of sound arrangement of wind, reed and string instruments would not be understood as were these strains in days of yore, when heard by toilers under the roof of an old saw mill.

Crude water powered mills for sawing lumber and for grinding grain made their first appearance in the section now known as Sullivan County, about 1800. Saw mills outnumbered grist mills in the ration of 10 to 1. Every airy dream of founding a town seemed to be built around a saw mill, a primitive arrangement--powered by an overshot water wheel which gave slow motion to an up-and-down saw which cut perhaps 1000 feet of lumber for ten hours of work per day. But these were the forbearers of the giant industry that gave prosperity to Sullivan County for a century.

In the year 1850, Isaac Lippincott and his son Augustus acquired a tract of land consisting of eight hundred acres, formerly park of the Hill holdings; and for ten years they cut and rafted the virgin pine down the Sock. They built four primitive houses and a store. One mile below Hillsgrove anti-dating this mill was one belonging to John Hill located where the church now stands and powered by water brought from mill creek by a race. Much of this land was purchased in the early sixties by Richard Biddle and Benjamin Huckell and is still in possession of grand children to the fourth generation.

The first steam whistle in the county sounded from a mill built by Michael Meylert at Laporte in 1850. During the next 100 years it was answered by portable mills in every locality within its borders. The ruins of disused water mills became themes for memories, pictures, poems and jokes. We recall strolling in the moonlight down by the old mill stream and finding the dam intact but the mill gone, and our gay companion quoting the ancient pleasantry: “Here is a dam by a mill site, but no mill by a dam site.”

Better railroads facilities in the eighties encouraged the building of big mills in the eastern section of the county. Lopez became a famous lumber town in song and story after J. S. Hoffa of Dushore built a large mill there in 1886. In 1888 the Hoffa interests were bought by the Jenning brothers, and Trexler and Terrill moved their mill from its location on Painter Den Creek to Lopez.

Jennings Bros. Then consolidated their mill on Taylor Creek near Seaman’s Hotel with the one at Lopez, and built factories to convert wastage into such products as kindling wood, clothes pins, broom handles, baseball bats, staves, washboards, matches and many other articles, many of which have been replaced today with plastics. The Jennings mill, factories, railroad and logging operation in 1900 provided employment for 600 men and gave Lopez a population of 1200.

Editor's Note: In 1899, the Jennings brothers began to relocate their enterprises to Maryland and West Virginia, where the forests had not yet been cut and opprotunities remained for a growth lumber industry. You can read the history of one such enterprise in West Virginia at Keith Allen's History of Jenningston.

Ricketts, in 1891, mushroomed around a big mill built by the Albert Lewis Lumber Co. It employed 150 men. The same year Trexler and Terrill built a mill large enough to have a daily capacity of 100,000 feet, also a stave factory and excelsior mill employing 150 men and a few girls.

Ricketts and Jamison City are divided by the county line and, though the mills themselves may have been located in Wyoming County, 80% of the logs they used came from the forests of Sullivan. The virgin timber that supplied these mills was exhausted in 1910 and the families that had known the kindness of these neighborly communities were scattered to who knows where?

No sign of human habitation remains at the bush grown site of Ricketts and there are few left in Jamison City, but the survivors and their descendents gather annually in a fond reunion and some of these perchance will go up on Red Rock Mountain where the government has located a radar project.

Editor's Note: In October 2004, we received the following e-mail message relate to the men in this picture: "During my last of many visits to your engaging site, I noted under SULLIVAN COUNTY INDUSTRIES Now and Then, a familiar picture. The man on the right, manning the cross saw is Herbert Leroy Farrar, the grandfather of my husband, Ira Bryan. Herbert had lived in the logging town of Masten, PA (now a ghost town). From family lore, the man observing was a salesman for the company who manufactured the saw they were using. Herbert was from Maine, having followed the lumbering enterprises to PA and Masten. He married Harriet Campbell, of Plunketts Creek Township, Lycoming County. Their daugher, Edith, married Benjamin F. Bryan, son of Benjamin H. and Philena Little Bryan of Hillsgrove, Sullivan County. Ira is Benjamin's son. Thanks to your efforts in providing us with this wealth of interesting items."-Evelyn McCarty Bryan, Picture Rocks, Lycoming County, PA.In 1886 the Lyon Lumber Co. started to operate a mill on Muncy Creek below Sonestown. By 1872 it was floating logs not only down the Creek but also down the outlet of Lewis Lake, now called Eagles Mere. The outlet of the lake may have had a geographical name, but locally it was always called “The Outlet”. This company continued in business until the end of the century. Their contractor and business manager was John Paulhamus, who served the father and later the son when Howard Lyons took over the business at his father’s death. Lyons made his home a short distance below Tivoli at Lyons Station, on the W. & N.B. just opposite the one saw mill he operated on Muncy Creek. Every day however, he took the morning train to Williamsport where the company’s offices were located.

Four splash dams helped to float the logs to this mill. One was a mile or so above Sonestown up The Outlet. The three in Muncy Creek were at Sonestown, Nordmont, and six miles above Nordmont at Mostellers. When all four of these dams poured their water into the valley below Sonestown it became flooded and roads were temporarily impassible. Two “cribs”, great rectangular, high box-like affairs of logs filled with stones, protected the banks from erosion and a long “boom” made of logs held together and looking like a string of huge beads fastened at the upper end, but loose below, also held the floating timber in check as it passed the towns and farms on the sides of Muncy Creek.

A “log job” was taken in the early Spring by some man with a little capital--very little sometimes--hoping to make more by this means. It meant that he and his family would move into a “shanty”, probably on North Mountain if the “job” was to end eventually on Muncy Creek, and board and lodge the 12 to 20 men he employed to cut down great trees, leaving a stump three or four feet high. They peeled the bark from these fallen trees and piled up the denuded logs to be taken to the mill. They ere usually piled near a “slide” or rollway where they were later hurtled down the mountain to the banks of the Creek. The “slides” were trough-like, made of logs and located at a very steep place on the hillside. Not the least dangerous of feats in the making of lumber was putting the logs into this hollow trough. They were used most often in the winter when snow made them more slippery and a log often jumped out and injured or perhaps killed the man whom it struck.

Once on the bank of the stream, the log awaited the “splash” to take it to the mill. If the contractor who took the “job” at a stipulated cost could get men cheaply enough, and not go to too much expense to feed them, he made a profit; otherwise he “come out behind,” as the localism had it.

In 1901 the Charles W. Sones Lumber Company built a big mill on Kettle Creek *, and in ten years had practically denuded the western section of the county of timber. They later sold the mill to the Central Pennsylvania Lumber Company, whose mills were at Masten and Laquin. This added another ten years to the industry before the coming of the turbulent 30’s and the worst depression America has ever known.

* Editor's Note: The land forested on Kettle Creek later became the venue for the Kettle Creek Fishing and Game Club in the 1920s. Click on the preceding link to read the history of the club, and to learn more about the Sones lumber enterprise in the area, You will also see some informative photos there.

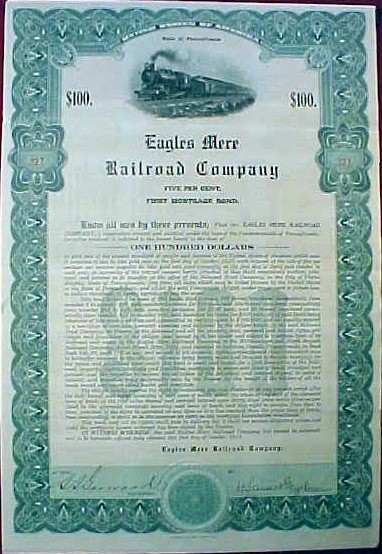

“Charlie” Sones made further Adventures in lumbering, buying vast tracts of forest land, shipping its products down the Eagles Mere Railroad. Unmarried, he was something of a philanthropist to the deserving youth, albeit in a quiet way, and despite his wealth, retained his comradeship with old friends made when he was a bookkeeper for the Lyon Lumber Co. He often visited Sonestown with L. R. Gavitt, whose political influence though considerable in Sullivan county, did not mean much in Lycoming where Sones resided and from which county he was elected State Senator. His favorite investment was in farms, and on one of these near Halls Station, members of the Williamsport Consistory usually ended their June meetings with a mammoth picnic as guests of Mr. Sones, who was himself a 32nd degree Mason.

Forests were the foundation of Sullivan’s prosperity. In the beginning settlers were attracted to Davidson township by its maple trees that yielded sugar. From Columbia county men made an annual pilgrimage and stayed through the sugar making season; later some of them cam to stay when they found that they could make a living the rest of the year. One story is told of the Irishman Bradley who arrived later than other settlers, fresh from the old country in the Spring and deemed his neighbors lazy louts who pursued sugar making only a short time then stopped. “Begora”, said he, “I ain’t goin’ to quit like they do. I’m goin’ to keep on makin’ sugar all summer.”

Early sugar making is a story in itself, with its outdoor fires to boil the sap carried by hand from spile to kettle. It did no damage to the trees and only when maple lumber became worth more that the sugar did men sell their groves of maple trees. Lumber meant more than board feet. Its by-products were equally valuable. Its bark caused the importation of hides and the establishment of tanneries. Coal mining depended on planking props, cars and railroad ties for operation. Its wastage has already been named as embracing everything from a match box to big box, and not the least of these were the articles of household furniture such as chairs tables and chests, often hand made outside of the furniture factory which was a wooden building as were most of the houses and the shanties which sheltered the laborers who brought the giant logs to the mill.

The woodsman’s day was usually from “can see” to “can’t see”, that is, from dawn to dark. His only holidays were Christmas, “ The “Fourth”, and such rainy days as perforce kept him indoors. He was skillful in the use of his tools, but behind the skill was main strength, and to maintain that power he ate and drank he-man food from three to five times a day, according to his labor and the length of the day. Frequently in season he stretched the time at both ends. If the water was high, or the snow deep, no hour was wasted. Logs that must be moved and bark that must be peeled could not wait for favorable conditions. If the logs were too far from a stream to be floated to the mill, the loggers drove their yoke of oxen into the forest, tethered them at a safe distance, felled and trimmed the tree with sharp axes and sawed it into length the oxen could drag. They then hitched the oxen to the log, goaded them into high gear, perhaps as much as one mile per hour, delivered the logs to the saw mill and went back for more.

Through this system passed with the pine in the 1870’s the stumps have survived a century and are still to be found among the second growth in parts of our county, even as are the stumps that resulted from somewhat more modern methods of a half century ago. By comparison, a tractor load of second growth, knotty pine logs twelve inches in diameter, delivered at a saw mill, brings twelve times more money today than did the virgin pine delivered by old methods which would require a month for delivery. If virgin pine existed in Sullivan county today, the owner would receive about thirty times as much per 1000 feet.

When pine was gone, the mills used peeled hemlock. Incidentally, the hemlock bark was used by tanneries whose number grew as the supply of bark, which was worth $2.00 per cord, increased. Hemlock logs were used by mills thirty miles down the Sock, mills with band saws that were driven by steam, and later gang saws that would cut 100,000 feet of lumber every day. This called for quick transportation of logs. At flood the Sock ran twenty miles per hour. This called for splash dams and log drives such as were found in Muncy Creek. But the swift Sock also carried lumber by raft down the river to Harrisburg and even farther.

Few are left to remember just how lumber was carried by hand, laid down in water, pegged together with wooden pins driven through holes bored by two-handed augurs; how layer upon layer was added until the raft carried 40,000 feet or more. Giant oars were placed fore and aft, and the strength and skill required to build a raft and float it to market added up to a sum total of hard work and the risk of losing life or limb. Then the brief thrill of running the raft down the stream! All this seemed small in comparison with the slow and painstaking labor of tearing down the raft, piling the lumber on the bank and selling it in competition with city slickers at from three to four dollars per thousand. It sounds like highway robbery and explains why men and teams back home worked for $2.00 a day or less, and why they were frequently deprived of this pittance by the friend or neighbor who had risked his all and failed.

The late Dr. J. Newton Osler, in the last days of his retirement (remembering the strenuous years of his youth), built a model lumber raft--a replica of those floated down the Sock and the Muncy in the period from the early forties to the late eighties. The model is owned and exhibited by his nephew, Otto Little, prosperous lumber dealer and builder of Benton, Pa.

This model will eventually find an honored place in the Sullivan Historical Museum and become a lasting tribute to its builder and to the men who have engaged in so hazardous a vocation.

Volumes could be written about the adventures of these distant days. Few survive who have had the opportunity to listen with starry eyes to the thrilling tales told by their sires. There is only one man left who actually participated in this watery drama, daring its perils and enjoying its thrills. He is William Rogers of Laporte, now more than eighty years of age.

Numerous fortunes for land grabbers and speculators were made by the lumbering industry, but no Loyal Sock raftsmen were in this class so favored. Their riches lay in their adventures, and their fame is in the thrilling tales of toil that makes glamorous an age that we, in this day of labor-saving devices, know only in memory.

No more the shanty man in his caulked shoes and picturesque clothes, the tannery man with the diversified odors of his calling clinging to his person like perfume. But different, oh so different! The acid factory worker with scents almost as obnoxious, and the miner, black faced and soot encrusted, with his sweetheart the mine mule. They are seen no more in all the land; but we are refreshed by the Paul Bunyan-like tales of their endurance, their hardships, the dangers at which they laughed.

To summarize the successive epochs of Sullivan County’s fundamental industry: Ox, yoke, chain and two-wheeled cart were crowed out by horses, harness, and four-wheeled wagons. In turn, they were replaced by steam winder, steam engine, narrow gauge track and crude log cars; then coal took the place of wood for fuel: gasoline gradually was substituted for coal and motor powered gasoline tractors and trucks with solid rubber tires superceded steam. Road construction with back-breaking mattocks-- better known as grubbing hoes--was taken over by bulldozers and made the continued use of axes and cross cut saws unnecessary. Log drives and lumber rafting gave way to railroads--a speedier and safer means of transportation. Now oil and electricity have triumphed over steam, and the end is not yet.

But among us are some who die hard, who love to picture the “good old days,” when men were men and women were women, proud of their lords and masters and obedient to them. Or were they?

Every commercial enterprise is the lengthened shadow of a genius in organization and leadership. Let us glace at some of the men of local industry who have seen visions and translated them into forgotten achievements in the Loyal Sock watershed.

First of these captains was Bill Gouty in the seventies. He fed his men well. He paid them generously, and enforced discipline by his iron will and two rude and ever ready fists. He logged tracts of land near the village of Hillsgrove on Slab Run and Mill Creek, driving logs down both streams and down the Sock to Montoursville. He drank whiskey straight and drove a team of vicious horses. When apprehended by the Williamsport police for driving on city streets in a manner they considered dangerous, he usually paid twice the amount of fine imposed, informing the judge that he intended to leave town with the same speed. He left mysteriously in the late seventies and was last heard from in the wide open spaces of what was then the distant West. His quiet wife conducted a temperance hotel for many years at Barbours Mills.

Gouty was followed in the eighties by Roaring Jack Campbell, a man respected for his honest dealing and clean living, though prone to talk loud when excited. This was undoubtedly responsible for the nickname--a badge of honor among all good and true woodsmen. Mr. Campbell built two splash dams on Mill Creek and drove logs down that rock-bound stream until the nineties.

The year 1880 brought to Sullivan County a Canadian, Robert McEwan, who became a citizen of the United States as soon as that honor could be legally acquired. The year 1865 found him a laborer in the old Dodge Saw Mill in Williamsport, and the next few years gave him liberal instruction in the art of rafting and floating logs on the Susquehanna.

At the age of 19 he was a sub-contractor; at twenty-four, an independent contractor in the Pocono Mountains employed by the Jay Gould interests in tanning and lumbering. On the Sock he served the Pardee and Emery Companies. His life is a real epic of lumbering; it calls to memory lumber camps, log slides, log drives, splash dams, rough and tumble rollways, floating arks and all the thrills that their names imply.

Robert McEwan never learned to swim; he was ever a white water man, but he pitted his strength and agility against depth and current along with the most daring of his jam breakers. In 1885 he experienced a near tragedy and was carried by his workers and neighbors on a stretcher eight miles from the lumber camp to his home in Hillsgrove. Though suffering from a broken pelvis he soon resumed his duties with the aid of crutches and his faithful horse “Bay Dan.” Forty to a hundred men depended upon him for employment. He bought about 200 horses and used them humanely. He paid a million dollars for supplies to equip and feed his crews whose wages totaled to sums beyond the conception of the average citizen, even in these days of inflated values.

For sixty-six years he directed labor in the forests of Pennsylvania, twenty-five of them with the local industry. His success is outstanding in comparison with the failure of many of his contemporaries. It is estimated that the number of board feet of lumber driven down the Sock by his efforts would be at least 200,000,000 feet, and through all the marketable wealth he produced made millionaires of its owners, his own share was modest. His family enjoyed the comforts of a healthful life with no display of ostentation or special social distinction, and men who spent the best years of their life in his employ saved enough to insure a comfortable living and restful old age.

Other men of the eighties and nineties doing contract work included Henry Hulzsower, John Brey, James and Osborn Dutter, Lewis Wager, Miles Jenkins, Joseph Bachle, William Brong, Jud and Harry Rodgers, and later George Walker, who became the connecting link between the old and the new when log drives went out and railroads came into the Hillsgrove area.

Elkland men of the period were Jerry Osler, John Webster, Avery T. Molyneaux, John Rogers, John Wheeler and August Plotts, Jonathan, Edward and Sumner Rodgers.

In Forks Township two well remembered names connected with lumbering are those of Lyle Grange and George Ball. Lyle Grange was a man of might, skill and endurance. His record for sustained quality and quantity of bark peel in a season has never been equaled. It took two exceptionally skilled men to peel and pitch to the skid road four cords of bark in a long days labor. Lyle Grange and his helper, DeWitt Morsey, averaged four times that amount for every day worked in a fifty day season. He has yet another modest claim to renown, for he is the father of Harold “Red” Grange, internationally known football champion, who is proud of his birth and rearing in Sullivan County.

George Ball, the other man of distinction, lost his life in March of 1897 while breaking log jams on the Big Sock. His body was carried ten miles by the current and not recovered until the following August, in the deep back-waters of the big splash dam.

Another “Creek” man to lose his life on Muncy Creek was Isaac Wilson. He was carried through the open gate of the splash dam at the beginning of a drive. His widow assisted in the search for his body which was found months later far below the dam. Muncy Creek is so much smaller than the Sock that there is not such a roll of workers as are named on the Loyal Sock. One of the well remembered names there is Kiess; two brothers, Joe and John, were employed. Joe was boss and lived in Sonestown in the last days of the log drives.

There are many others whose names are now in possession of the Recording Angel. The boys who visited the camps remember best the stalwart forms and excellent meals there. Most of them have forgotten facts they learned there, one of which is that Sullivan County homes were built from Sullivan County lumber, and that every farmer built his hose and outbuildings from lumber cut on his own land, and paid carpenters, masons and painters with money derived from the sale of logs and hemlock bark. The same is true of 90% of the original homes in Sullivan County.

After exhausting all available virgin timber that could be profitably manufactured the big mills moved South. Small portable mills salvaged the partly decayed wastage for pulp wood, mine planks and various uses required short lengths of lumber. Tracts of land from which lumber is harvested revert to the state if not sold for unpaid taxes.

Second growth lumbering had its inception with the Citizens Conservation Camp in the turbulent thirties. These were located on Mill Creek and Dry Run, near Hillsgrove and Jakersville * and Laporte. They housed about one hundred men each and teamed with P.W.A. labor covered the county. The P.W.A. and C.C.C. are institutions we, as a nation, would like to forget; they were non-profit relief measures that gave sustenance to stranded youth of families on Federal relief. They came from all parts of the state; few if any remained; their work resulted in establishing recreation areas where the wreck and ruin of lumbering had created havoc. In these areas the Department of Forest and Waters is stressing the need for sane conservation by enforcing restriction in timber cutting, planting trees and propagating wild life. This has given a new beauty to State forest, providing revenue from the sale of standing timber, and brought prosperity to the revived lumber industry.

* Editor's Note: The CCC camp at Jakersville actually had their own camp newspaper, the Jakersville Echo. In the February 28, 1935 issue (Vol. II, No. 16), John Sweeny (sic) authored a poem "To the President" entitled Life is What You Make It:Just take this tip from me,

For I like many others,

Have become a C.C.C.

Yes SIr, we knew its meaning,

Its very plain to see,

We are going to be the best of men

When we leave the C.C.C.

What power has changed our vision?

What light now shines for me?

'Tis a ray of light from Heaven,

Is the U.S. C.C.C.

And long may it continue,

In a fervent prayer from me;

And may God protect our President,

The father of the C. C.C.

It is not known for sure if John was actually John W. Sweeney (1870-1947), son of Martin and Julia (Wright) Sweeney, who lived on a narby farm in Ringdale. However, his family had for generations been part-time lumberjacks, so he would have been familiar with the types of work available in these camps and may well have been trying to find additoinal income in the midst of the Depression. John Sweeney was the brother of Peter Francis Sweeney (1878-1934), grandfather of Bob Sweeney, this site's administrator.Among modern pioneers experimenting with new methods of lumbering can be listed the Ed Flynn Lumber Co. with saw mills at Lopez and Ringdale. More than a million feet are manufactured annually and delivered from tree to trade by motorized oxen. For strength and speed this would put Paul Bunyan and his blue ox in the juvenile class.

Hon. Walter Baumonk has factories at Forksville. He is interested in the Muncy Valley Industries; he cuts and uses more than a million feet of lumber in the making of reels, boxes, and sundry articles demanded by commerce. Modern saw mills, some of one million feet annual capacity, are scattered over the county in Hillsgrove Township. Gleason Lewis operates a large mill and uses much of his produce in the construction of vacation cottages. Westley Leonard owns a mill, temporarily leased to Henry F. Buck. Harry Ketchum and Robert Brown operate a mill and wood working factory at Lincoln Falls. There is also the Keith McCarty mill near Estrella, the Roscoe Burgis mill at Bethel, the Guy Baldwin mill at Muncy Valley and the Keneth Rose mill at Laporte; and in every township small mills that are run when logs are available.

Lest we forget, may we mention the autocrats of the woods, the log scales. These experts estimated board feet in standing timber, surveyed roads and decided best methods of moving logs to streams. Methods included sleds and teams, rough and tumble rollways, slides and splash dams. They were the law between jobber and owner, reporting logs left by jobbers, first to the jobber then to the owner. Though they have had much unmerited criticism, they were usually respected.

Saw Mills, on the Sock or its branches, that provided employment for many heads of families from 1880 to 1920 were the D. D. Brown mills and logging operations in Laporte and Colley Townships, the Reeder mill five miles below Hillsgrove, with enough shanties occupied by their workers to require a temporary school and post office. This mill was later moved close to Laporte on the road to Forksville. The Jakersville Mill is on the Commons near Ringdale. Jakersville was named from the favorite byword of the founder John Webster, “By Jakers!” The Chas. Sones interests took over and by 1910 had stripped the woods of all marketable timber. A present day by-product of mills is stove wood cut from mill wastage, sold at reasonable prices and donated to small churches needing occasional heat.

Laquin

Lumber Town on Schrader Creek

Bradford County, PA

Undated Old Postcard

Photo courtesy of Deb WilsonLaquin, a ghost town just over the north county line in Bradford County, flourished from 1908 to 1920. Its wood mills were kept buy with logs cut from the last virgin timber in Sullivan County. Several native woodsmen and their families lived there. Twenty years have passed since the last lumber camp was razed for second-hand lumber. The enclosed verses, author unknown, were found hidden and forgotten among the ruins. It may contain more truth than poetry or more exaggerated imagination than truth according to the viewpoint and memory of the reader. Names have been changed to "Doe" when references are uncomplimentary.

A PEN PICTURE OF LAQUIN, PENNSYLVANIA

Now I’ll spin you a yarn of a town called Laquin,

Through if ‘twas named Hell it would not be a sin;

For of all the bum places I ever have seen,

This town on the Schrader is surely the Queen.

Schrader Creek

Near Laquin, PA

Old Postcard Dated 1911

Photo courtesy of Deb Wilson‘Twas built in this valley on account of the mill,

And if it had a wall round it, ‘twould beat Cherry Hill.

For they work for their board here and buy their own clothes,

And they’re covered with soot from their head to their toes.

Now the streets here are paved, you can bet they are nice,

In summer it’s mud; and in winter it’s ice;

And the nights here are black as the hinges of hell,

And if one takes sick here he never gets well.

There’s a plant in this town, it’s called the stave mill,

It’s way up the track at the foot of the hill;

And if I were to tell you what these men have to do,

When you get to Laquin you would surely pass through.

Then there’s the big mill, and the hub factory, too,

And the kindling wood joint where the dress in blue.

They are just alike right down to a man;

They will take the last drop of your blood if they can.

And of Sherman’s Distillery a verse I will sing;

They make liquor of basswood or any old thing.

That the men drink it days and keep fire with it nights

But it beats Laquin whiskey so far out of sight.

Now there are, of course, some good men in this place.

And some awful specimens of God’s human race;

And if the plain truth of these people you say,

They all live in Laquin for they can’t get away.

A doctor lives here and his name is John Doe,

He measures his dope always just so.

And he’ll send you a bill that you never could pay

If you worked in this town “till your hair all turned gray.

Another John Doe is a wonderful man,

Who does for the Company all that he can:

For he’s built him a mansion far up on the hill,

So he gets a good view of the men at the mill.

Then there’s also John Doe who came from the South,

You wouldn’t think butter could melt in his mouth.

He will give you a job, if you’ll trade at his store;

You know what that means, so I’ll say no more.

General Store

Laquin, PA

First View

Undated Old Postcard

Photo courtesy of Deb Wilson

Original was posted on eBay

General Store

Laquin, PA

Second View

Undated Old Postcard

Photo courtesy of Deb WilsonNow a company store is, of course, ‘gainst the law,

And this one’s the worst that the world ever saw;

For they’ll double the treble on goods that they sell,

And if this crew don’t get there, there’s no use of a hell.

Well, the men here aren’t suited, at least so they say,

And I guess it’s the truth, from the wages they pay.

It’s a dollar and fifty; go look where you will;

A man could do better in a old shingle mill.

For they hire Italians and Huns by the score;

A white man can’t get a job there anymore;

And if there’s a chance they will give you the run

And fill your place with an Italian or Hun.

And the time they keep is a sin and a shame;

They work these poor Huns in the snow and the rain,

And they expect to keep running for a hundred years more,

Till they clean up Hungary and Italy’s shore.

But there’s Leo McRaff, no harm would he do

And good Arthur Snell and Jack Anderson, too,

And Rockwell and Bademan are square as a brick,

Now on such men as these, we’ve no reason to kick.

And there’s Ellison Bennett, from Towanda he hails,

He’s a sawer of boards and a driver of nails.

At building new houses he’s going a fright;

It’s blueprint in the morning and you move in at night.

And we’ll mention Sam Doe, he’s a dealer in beef

If you buy meat of him you will soon come to grief;

For the steers that he sells and guarantees fat

Are bull meat unloaded at Mount Ararat.

Then there’s another fellow, it’s butter he brings,

And pork and potatoes and lots of such things.

There’s more we might mention but what good would it do?

For hucksters in general are a dishonest crew.

Then there is Fred Flick, drives the Company’s blacks;

He goes ‘round through the streets as if hitched to a hack.

He’s the nearest the thing, so the girls here all say,

That they’ve seen in Laquin for many a day.

Now ladies in Laquin are fair as the rose,

And why they all stay here, God only knows;

If they lived in Cold Spring it wouldn’t seem queer,

Or in any old place just to get out of here.

Hotel Laquin

Laquin, PA

Undated Old Postcard

Photo courtesy of Deb Wilson

Original posted on eBayNow there’s a crib here that they call a hotel.

A man can’t live long on the stuff that they sell,

For they make their own whiskey, and brew their own beer;

And if Bull isn’t rich it is certainly queer.

On the Company’s camps the bark peelers kick,

And there’s one thing that’s certain; the bugs are too thick,

The cooks are all Dutch, you plainly can see;

And often you’ll get a bed-bug in your tea.

The men here in Laquin sometimes get so drunk,

That they don’t know whether they’re in Ralston or Shunk.

And the best thing to settle their poor muddled brains,

Is the coffee they get up at good Mrs. Kane’s.

Now this worthy lady was never afraid

Of any human being that God ever made;

But if a small mouse in the dining room’s seen.

She can jump on the table like a girl of sixteen.

And the girls that she keeps are good waiters and cooks.

They are jolly young people--you can tell by their looks,

For they serve you the grub in a way that’s so neat

That a corpse would get out of the coffin to eat.

Then there’s John Doe who runs another hash plant;

He’d take all the boarders in town but he can’t,

For his house is so full, I’ve heard it said

That they now have to put three or four in a bed.

And there’s Board Master Barnes, a God-fearing man,

For he gives us fish whenever he can,

And if he was able much more would he so,

But the boarders he got are the devil’s own crew.

Main Street

Laquin, PA

Undated Old Postcard

Showing Both Churches

Photo courtesy of Deb Wilson

Original posted on ebayNow to save the whole town from utter disgrace

They are building a church or two in this place ,

And they’ll convert these poor heathen for one dollar per head

And guarantee them they will wear wings when they’re dead.

The Baptist preacher, from Elmira came,

As a builder of churches he get there just the same!

The ground is now broken and the church under way,

And we expect the new spire to be seen any day.

And the Methodists too, are not far behind, *

They are getting things fixed just about to their mind.

Their chaplain’s named Miller: he’s a Burlington man

And he’ll put a ringer in here if he can.

* Editor's Note:Since the photo of the completed Methodist Church shown below is on a postcard dated to late 1907, this poem must hae been written before then.These city bred preachers will call at your place,

And they’ll read in the Bible with a long solemn face;

They will ask you to church where they’ll pray and they’ll sing,

But when they get home they’ll do any old thing.

Now these sinners in Laquin are doubtless the cream

Of any in the country that ever were seen.

And if they can get them here so they’ll hear a church bell,

They can tackle any place this side of hell.

For we wicked old hicks must someday walk the plank,

And the chances are that we’ll all draw a blank.

But if Gabriel should give us an old harp with one string,

We’ll just do our best with the angels to sing.

But if we had the choice of going to hell,

Or staying on here for a much longer spell;

We would get out of town on the first sulphur train;

For if you die in Laquin you go there just the same.

Now on the things past it’s no use to repine,

Though we’ve squandered our money on women and wine.

If we had it all back, we would borrow some more

And buy a through ticket to Africa’s shore.

And if I should live till I draw a full pay,

I’d leave this blamed town on that very same day,

And I’d hit the old hay road to York State once more

And bid farewell forever to the Schrader’s cold shore.

Methodist Church

Laquin, PA

Old Postcard with Posting Date of December 27, 1907

Photo courtesy of Deb WilsonThis unfinished work is a labor of love, accomplished by a hard work, time and money given by us to the fulfillment of our dreams and it is our fond hope that future generations may add chapters when we of today shall be forgot.

“The old trees fall, but the young trees stand,

Even as you and I;

Stand in the stead of the pioneers

Who builded here in their fruitful years,

A faith that will never die.

So long as the pines shelter sprouting cones

The forests will never die;

The old will pass on to their sturdy young

The dreams they cherished, the songs they sung;

Even as you and I.”

John Stabryla

Coal Miner

Born December 29, 1889 in Grabowka, Poland, he migrated to America via the Prinz Oskar, through the port of Philadelphia on August 5, 1913. From there he found his way to Chicago, where he worked in the stockyards, went to barber school and had this photo taken. He came back east to Centre County, PA, where he met and married Mary Mihalik on June 18, 1918. They had three children. Then, sometime between late 1922 – early 1923, they moved to Bernice, PA. John worked in the mines at Bernice and they had eight more children. John passed away July 18, 1948. Mary passed away on September 19, 1995. They are both buried in St. Francis Cemetery in Mildred. Their children were John Stabrylla, Helen Morrissey, Agnes Zwanka, Anne Abbott, Pauline Themas, Veronica Gallagher, Frank J. Stabryla, Mary Hargrove, Joseph Stabryla and Blanche O’Brien. You can also learn more about the Stabryla and related families at the Stabryla Family Research Project.

Photo courtesy of Jim Stabryla, John's grandson via Frank and Ann Marie (Coyle) Stabryla.DOWN IN THE COAL MINES

“Down in the coal mines underneath the ground,

Digging dusty diamonds all the year around.”This ditty of driver boys whose sweetheart was a mule in the mines seems a fitting introduction to the record of an industry that through the years has brought to the world light, heat and power mixed with comedy and tragedy.

We in old Sullivan, who shared the toil and tears that were the fruit of our labor, go together down the drift of time, carrying in our caps the flickering lamp of memory in the hope of meeting and greeting men and boys who shared with us the peril of our vocation. May we hear again the kindly advice of the gray-haired miner for whom we loaded coal into a mine car - - “Have no fear, me lad. All we need to work in the mines is strong body and a weak mind.” Yet underneath this rough exterior was a heart of gold, set with gems of purest ray that sparked in sympathy for those in sorrow when tragedy was the lot of a fellow worker.

In early days, before safety devices and sane laws gave a measure of protection to workers in coal mines, every ton of coal sold was stained with human blood. Sullivan’s mines can thank a kind Providence for fewer accidents than fate brought to the other regions around us, and no major disasters cast a gloom over our past. Perhaps we are nearer to the men and mules that moved the coal than to the pioneer management that developed the industry. But records and tradition prove them to have been men of willing spirit that inspired them to deal justly with their fellows in the ranks of toil.

The late Myron Wilcox laid claim to be the first to find coal in the Bernice area. No definite date of discovery or opening of a drift known to the Shields, or Milheim drift, is recorded, but related happenings place it in the late sixties. This was an outcropping on lands formerly owned by Michael Meylert, later by Hon. George D. Jackson of Dushore. The coal was sold locally in lump size.

In 1871, the first Bernice breaker, modern at the time, was erected, and chestnut and pea coal in carload lots was prepared for Eastern Markets and shipped over the recently completed State Line and Sullivan Railroad. The moving spirit in developing this industry, the spine of local property for more than a century, was George D. Jackson. The village of Bernice and all of the buildings, company owned, grew around the breaker and was named for his wife. The eighteen years of his management were marked by friendly labor relations, proved by the fact that he was elected to the State Assembly in 1858 and re-elected each term until promoted to the Senate in 1866; continuing in office until 1879 when he died at the age of 52 years. His widow, Mrs. Bernice Jackson, carried on his works of charity and benevolence until her death in 1899. From these small beginnings, until the purchase of the property in 1903 by the Connell Mining Company, the enterprise had grown until three hundred men were employed. In 1898, Walter B. Gunton leased a large tract at coal lands from the Jackson heirs, built a new breaker and developed a profitable business. It lasted until 1906 when the supply was exhausted.

A few mine shacks of the period were built near the breaker but most of the mine families owned their homes in Mildred or lived on adjacent farms. These shacks were later bought by enterprising citizens and reconditioned into modern homes with present day conveniences.

Other mines in the Bernice area were the O’Boyle and Foy, a shaft mine opened near the Murray, a sizable breaker. Twelve miners’ homes were built and one hundred and fifty men employed. It was sub-leased to the Connell interests in 1915 and the workings dismantled with no trace remaining. The Pee Wee Mine, employing forty workers, was opened by Randall and Schaad but shared the fate of the O’Boyle and Foy. A small outcropping on Ketchum Run in Forks Township, known as Mercur Mine, was operated on and off for thirty years by one or two contracts miners; the coal was sold by sled load in winter to the rural trade. The Forksville Mine near Forksville was opened in 1943 and closed in 1951.

Murraytown About 1900

The community at this time had about two dozen company houses, a store, and offices of the Murray mines. Lopez and the Murray coal breaker would be off camera to the left. The O’Boyle breaker is in the distance in the middle of the picture. Reportedly, only four houses were still standing in early 2007. This view is toward the north in the direction of Bernice and Mildred.

Source: A photo from the Joe Tabor Collection

Reprinted in the Sullivan Review, January 25, 2007The Murray Mines

A coal development within the memory of many present residents of our county was a big coal breaker and town built at Murraytown in the woods, one and a half miles from Lopez in 1901. This was park of the inception, growth, fall and decline of the Northern Anthracite Coal company for three decades. Scranton capital , in which Anthony J, and Michael J. Murray with P. H. Mongan held a controlling interest; leased a large tract of coal lands and built the largest breaker ever built in Sullivan County. One hundred sixty-nine feet high, with the steep inclined plane reaching from the mine shaft to the top of the breaker, it was an impressing sight. The town of Murray was superior to the surrounding towns. It consisted of twenty-five large comfortable houses, painted red, a big company building, housing three apartments, and the Murray Store and Post Office. This building is now a ruin.

The company headquarters were in Dunmore. During the construction, no roads existed except those brushed out by the builders, all building material was hauled with teams from Lopez. The W. N. B. Railroad laid a switch from the Lehigh Valley at Lopez to the Murray Mines in 1902.

In balmy days the carload shipments averaged 1,000 tons daily, with no account of wagon loads sold locally or coal used by the company’s power plant. Four hundred and thirty men and boys were employed at the peak in 1919 bi-monthly payroll exceeded $50,000. The enterprise flourished for more than twenty years with few slack periods until the coal strike of 1922 when the tide water markets were lost and the big veins gave out, leaving only shallow veins that could not be mined profitably. After 33 years, marked by honest dealing and fair treatment of their working partners, the Murrays abandoned the project. Murraytown is rapidly wasting away. The breaker fell into decay and late one night in 1935, during a summer windstorm it crashed to the ground, its rubble a monument to the success rather than failure of builders of history who will ever be held in high esteem. The names of men and their families that made Murray a good place to rear children are A. J. Murray, Incorporated and Mine Superintendent with his brother M. J. Murray as Mine Foreman. Later P. J. Murray and Peter P. Murray, sons of the Superintendent were Department Superintendents. Martin Lynch held the distinction of having the largest family living in Murray. Breaker bosses were William Mongon, William Banfield, Patrick McGee, Mike Chassock, A. W. Murray, James Gilligan, Roy Sterline and Frank Hoag. John Bonci was hoisting engineer at the shaft.

Families living in company houses were headed by John and Adrian Roberts, Jim Waples, Tom Donahue, Marvin and Daniel Potter, Richard May, Henry and Thomas Fell, Henry Johnson, William McGee, John Collins, the Cahill and Fitzharris families, James R. and William James Walsh, Tom McAvoy, Theodore Beaver, William Gribbon, Patrick Lynoot (Mine Foreman) Sid Sullivan, John O’Boyle, Mat Clemmons, John Shelvin, Robert Beckel, Mike Marshall, Frank Gutosky, Thomas Hope, Andy O’Malley [see photo below *], the Hurly family, Joseph and James Lang, Orazio Bonci, Martin Casper, Stanley Burke, William Van Horn (8 sons in the first World War - 11 children), James Lavelle, John Linkosly, Clinton Hurst, ( Mine Foreman), William Thayer, Mike Donavan and the Kawhan family. These good men raised families, paid their bills and taxes, went to Church and did their civic duties as they saw them in the building of America. Where have good Americans done more?

Family of Andrew J. and Catherine J. O'Mallley

April 1909

Murraytown, Sullivan County, PA

Top, l to r: Irene J. (9/26/1897), Robert A. (4/3/1894), Gertrude C. (9/11/1895)

Middle: Andrew J. (3/15/1863), Mary E. (3/10/1900), Catherine J. (1/29/1873)

Bottom: Joseph J. (12/15/1905), William F. (4/25/1904), Anna K. (9/14/1908)

Note: Birth date in parentheses after each name. Andrew worked at the original Murray Mine near Wilkes-Barre before moving to Sullivan County. He was certified as a mine foreman. Catherine was born in "Weigand" (likely Wigan), England and came to the US at an early age. The children in the top and middle rows were all born in Avoca, PA near Wilkes-Barre; those in the bottom row in Murraytown.

Source: William O'Malley, April 1, 2011

Great grandson of Andrew and Catherine and grandson of WilliamThe Connell interests with a monthly payroll of $80,000, employed 600 men from 1903 to 1932 then went into the hands of receivers. The Sullivan Coal Company 1932 to 1936, whose promoters were T. V. McLaughlin and John Faroni, employed thirty miners. The Brown Breaker was in operation by Saulsberg and Brown of Wilkes-Barre from 1932 to 1940. These Companies exhausted the veins that could be profitably mined. The White Ash Coal Company, developed by Andrew Perinski and Kline Richie, is now owned and operated by William Monahan.

On the outside looking in one would be foolish to speculate upon the future of coal as an industy in America. In the local field mining engineers agree that the vast tonnage removed through the years has made little impression on the quantity remaining and awaiting development. Once the only dependable source of light and power for world manufacturing and transportation is now priced out of the market and in competition with electricity generated by white coal (water power) and (black gold) oil and its derivatives. In the unpredictable future all of these commodities may be crushed by the atom or other scientific creations yet undreamed. New uses may be found for coal, and colum and slate dumps, wastage of mining, bane of the present, maw bless our prosperity. We are content to allow future residents to adjust themselves to future conditions and happy to record this moving picture of past events for the information of men and women of tomorrow.

Ten Thousand Years In Sullivan County

Ralph Vitale, owner of the Exchange Hotel Building in Dushore is the proud owner of our native terra at least ten thousand years old and perhaps several centuries more, a fallen tree stump taken from a fall of rock in the Connell mines at Bernice in 1942. Through the years of toil Mr. Vitale earned his promotion from breaker boy to mine foreman.

The oversized roots would place the tree in a prehistoric swamp with roots above the ground; veins in the bark indicate that it belonged to the maple family; weight of the reconstructed stump and roots is estimated half a ton; the substance is slate with no coal visible.

Under the Hide

The bush-grown ruins or sites that for sixty years housed the next largest industry in the county have now been converted to other uses. Prodigal sons, returning to the haunts of their childhood, yearn for friends and days long gone when they view these places. The tanning of leather has ever been a task demanding skill, strength, endurance and patience. These qualities seem to be bred in generations following this vocation, emphasizing the fact that tanners, like poets, are born not made. Modern machinery, aided by time-saving and wonder working chemicals, have revolutionized the process until the method of leaching tannic acid from oak, hemlock and spruce bark has become a lost art. That modern processes are far superior, we concede, but they lack the tradition and romance of yester year, so dear to older hearts; thus we try occasionally to rescue them from the limbo of things forgotten.

May we turn back the clock of years to 1851 and commune with ghosts of men that worked in the Meylert Tannery at Laporte? We find fifty hides bought from local butchers soaking in wooden barrels filled with solutions of salt and lime. Thus the hair was loosened and removed with dull scrapers that did not injure the grain. This ancient plant may have boasted one leach for boiling ground hemlock bark into liquor and six vats for tanning hides; the hides were shifted by hand from vat to vat until tanned. If upper leather was made, the flesh was covered with a dry mixture of saltpeter and hard wood ashes and the grain smeared with Neatsfoot Oil and Mutton Tallow. The tanning and rubbing required from eight to ten months; rolling and polishing were done with wooden blocks and rollers cut from black lignumvitae, the hardest and heaviest wood known. The finished leather was sold locally and made by craftsmen into saddles, harness and shoes.

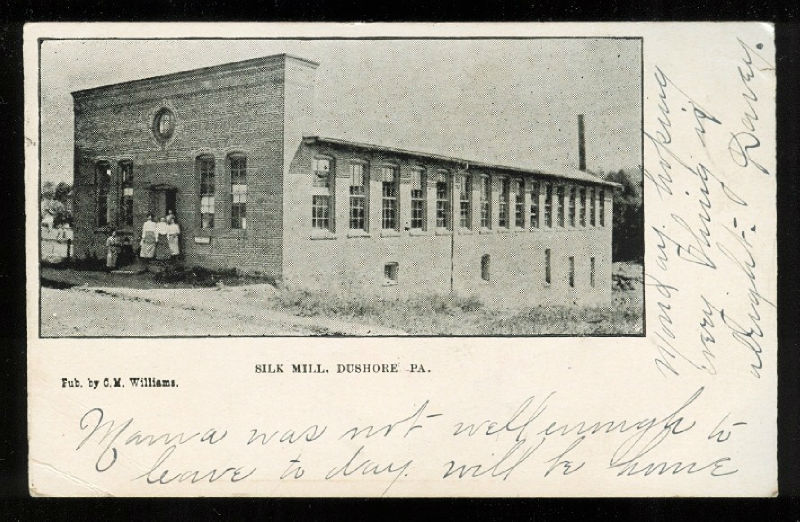

Bark was ground in mills located in the open air because of the dust that rose like smoke from the bark and were operated by horse power. In the years from 1860 to 1905 three tanneries located in Dushore tanned hides for pioneer families from cattle, horses, sheep and dogs killed on their own farms. Three families of tanners with few descendants left in the County were the Cornelius Cronan children and grand children. The building that they used was located on the hill side above Marsh Run near St. Basil’s Church. Ruins of the foundation indicate that it measured 40 by 60 feet and housed vats and sweat pit for loosening hair. The Hoffa tannery, occupying the lot where the Hoffa home is located, was built by Aaron Hoffa about 1860. His seven sons and four daughters provided needed labor. John S. Hoffa inherited the business and family responsibilities at the age of fourteen. These two plants passed out in the 1870’s. In 1875 a tannery was built by Charles Moyer near the site of the silk mill on Headly Ave. ** It was smaller than the Cronan and Hoffa tanneries. The project was abandoned in 1905. Surplus leather made in the Meylert, Cronan and Hoffa tanneries was sold in Muncy, during the Civil War, to shoemakers making boots for the U. S. Cavalry.

**Editor's Note: Silk became a growth industry in this part of northern Pennsylvania for about 40 years in the early 20th century. You can read about the Sullivan Silk Company further down this page. After the invention and introduction of synthetics and the eventual movement of textile production to cheaper venues, silk manufacturing activity in the area came to an end. Here, for example, is an announcement made in 1905 that relates to the plans by three prominent local businessmen to go into the silk industry:

Sullivan Herald

Dushore, PA

August 16, 1905

Application For Charter

Notice is hereby given that an application will be made to the governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on Tuesday the 5th day of September A. D. 1905, by Samuel Cole, Alfred R. Morrison and Harry N. Bigger under the act of assembly of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, entitled "An act to provide for the incorporation and regulation of certain corporations." Approved April 29 1874, and the supplicants thereto, for the charter of an intended corporation to be called the "Loyal Sock Silk Company" the character and object of which is to manufacture and sell textile fabrics and for these purposes to have, possess and enjoy all the rights, benefits and privileges of said act of assembly and its supplicants,

John H. Cronin, Solicitor

Dushore, August 8, 1905

James

McFarlane purchased the Meylert in 1864; he enlarged and improved it, increased

the capacity to 100 hides or 200 sides of leather daily. Transportation of hides and leather to Muncy

gave steady work to four teamsters, driving covered wagons drawn by four big

mules. Four long days were required to

make the trip.

The

Thornedale Tannery, four miles east of Laporte, was built in 1868 by McFarlane

and Thorne & Co. Both plants grew

to capacities of 400 and 500 sides, and the time required to tan was reduced to

six months. The Thornedale tannery

closed in 1893 and was dismantled.

The

Hillsgrove Tannery, built in 1870 by Andrew Hawer, capacity 100 sides, was sold

in “74 to McFarelane and Thorne & Co. then sold to Hoyt Bros. of Sanford

Conn. In ‘78. The capacity then

increased to 500 sides. All of these

plants were bought in the Spring of 1892 by the United States Leather Trust,

and the industry that had prospered and grown steadily since its inception

began rapidly to decline. Watered stock

in the combine fluctuated and long periods of idleness in the plants caused

workers to move or lose their jobs.

Former owners of the plants who had accepted stock in lieu of cash lost

fortunes. Mismanagement and scarcity of

bark caused the Trust to abandon the business in 1922. Machinery and buildings were sold at junk

prices; tannery company homes were sold at $50.00 and razed for second hand

lumber.

The

Muncy Valley tannery was built in 1867 by L. R. Bump. It was a small affair with a capacity of 150 sides per day. After four years of operation it burned and

was later sold at Sheriff’s sale. D. T.

Stevens & Son bought it and ran it until in burned again in 1874. People of later years dated events from the

second fire “Before the tannery burned” and “After the tannery burned.” Putting out either fire would have been

impossible. Muncy Creek was at the

other end of the village and what little water the community used was deep in

the few wells. But Stevens & Son

rebuilt and carried on more business than before. The town grew with men moving into it from distant farms. Foreign labor for $1.35 per day attracted

workers. The output was then 750 sides per day. Muncy Valley was the largest town in that area in the 90’s, its

general store the best shopping center north of Hughesville.

Many of

the tannery employees were Polish. They

were on the same hillside as the church and parsonage, but lower down and

around a bend. Cottages behind the bark

stacks were occupied by native Americans.

At the turn of the century the population of the village was large

enough to demand three rooms in the school building with every seat filled, and

sometimes pupils standing on the floor or in corners.

The

number of Catholic families justified the celebration of Mass by priests from

Dushore and Blossburg. This was held in

the schoolhouse, the altar being kept meanwhile by the James Monan family in

their home. Before that time, one of

the resident’s company houses was used as a chapel. Of the 26 buildings occupied by foreign families this is the only

one standing. It is 85 years old and is

the present home as well as the birthplace of Mrs. Elizabeth Scarbeck

Angle. She is the last descendant of Polish

settlers in the valley. Mrs. Angle

remembers with pride that the first Mass celebrated in Muncy Valley was said in

her parents home, with Catholics of four nationalities in attendance. Throughout the years all rites of the Church

were performed here--marriages, funerals, baptism, confession and communion.

The censor, candle holders and the ancient bureau that served as an altar are

cherished heirlooms.

The

Tannery closed in 1909, and Muncy Valley for many years was a “ghost

town”. The Jamison City Tannery was

built in 1889 and sold to Thomas Procter.

It was similar in size and output to the Hillsgrove Tannery; most of the

bark used came from Sullivan County.

This tannery was sold to the Trust in 1902 and closed in 1909.

Thornedale, Laporte, Tannery Town and Hillsgrove became deserted

villages. Many of the workers had moved

to Endicott, N. Y., where good jobs awaited them and rapid advancement was the

rule. Buying homes, but cherished

memories often brought them back to their old friends in Sullivan on festive

occasions. Space permitting, three

thousand names could be added to this chronicle of real men who made history in

making leather in the five tanneries, but few of their posterity remain to give to their memory the tribute of a

smile. Three names are outstandingly

remembered for their achievements.

James McFarlane, practical, progressive and honest, established a record

as builder and virtual owner of two tanneries that won respect and recognition

in his field; James P. Miller,

efficient Superintendent of the Muncy Valley Tannery for thirty-seven years was

respected in his county and frequently called to counsel with tanners in

matters of experiment and management; George Darby, big in body , mind and

heart, devised a piecework system that equalized the work, raised wages and

shortened the work day. He came to

Hillsgrove with Hoyt Brothers and later added to his duties by managing the

largest tannery in the State, owned by Hoyt Bros. at Hoytville, Tioga County.

The July

1951 issue of “Now and Then”, magazine of the Muncy Historical Society, carries

a fine picture of a bark stack, once common at all five tanneries in the

country -- Laporte, Thornedale, Muncy Valley, Jamison City and Hillsgrove. The snapshot from which the cut was made was

loaned by Miss E. Wrede of Laporte.

The

shaping and roofing of a bark stack, two hundred feet long, twenty-four feet

wide and twenty feet to the eaves, was a liberal art requiring strength,

endurance and skill. Remembered artists

in this line were Jacob Fries of Laporte, Ezra Wagner, working his way through

a long course at Bucknell University, and John Lucas, immigrants from several

countries in Europe, the latter two were said to be able to roof stacks in

fifteen different languages.

The

history of tanning in Sullivan County is written and the books are balanced. To the most optimistic among us there seems

little hope of a revival. We, to whom

it brought joy and grief, miss the happy friendships made through its influence

and feel that the sentiments of all concerned can be best summarized in two

lines by Tennyson -- “’Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have

loved at all.”

In an

old copy of the Sullivan County Democrat appeared an advertisement that awoke

memories: “Hemlock pump logs for sale, one and a half inch bore, ten cents per

rod.” The logs were square or round,

six inches in diameter. They were

fastened in a revolving vise and a ten foot auger pushed into the center to

make the hole through which was pumped dirt to keep them in place. A present day youth would comment, “How

crude”, yet there was a time that villages and towns depended on this style of

conduit for their water supply.

The Emmons and

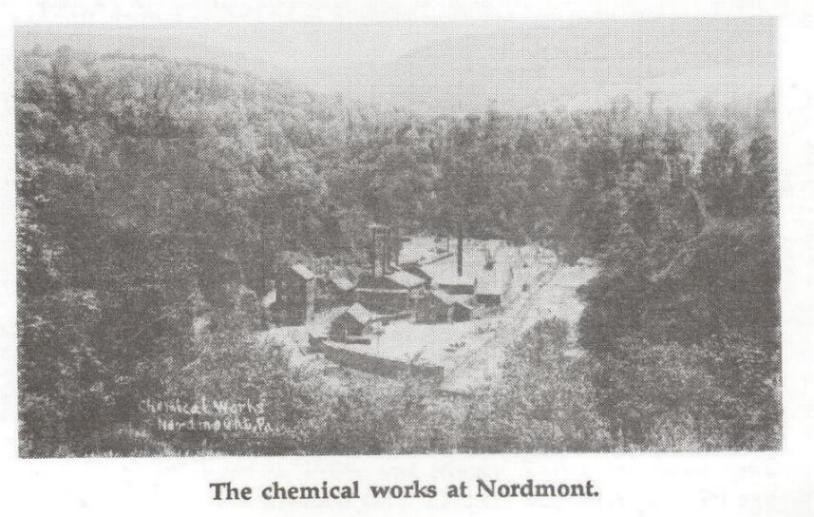

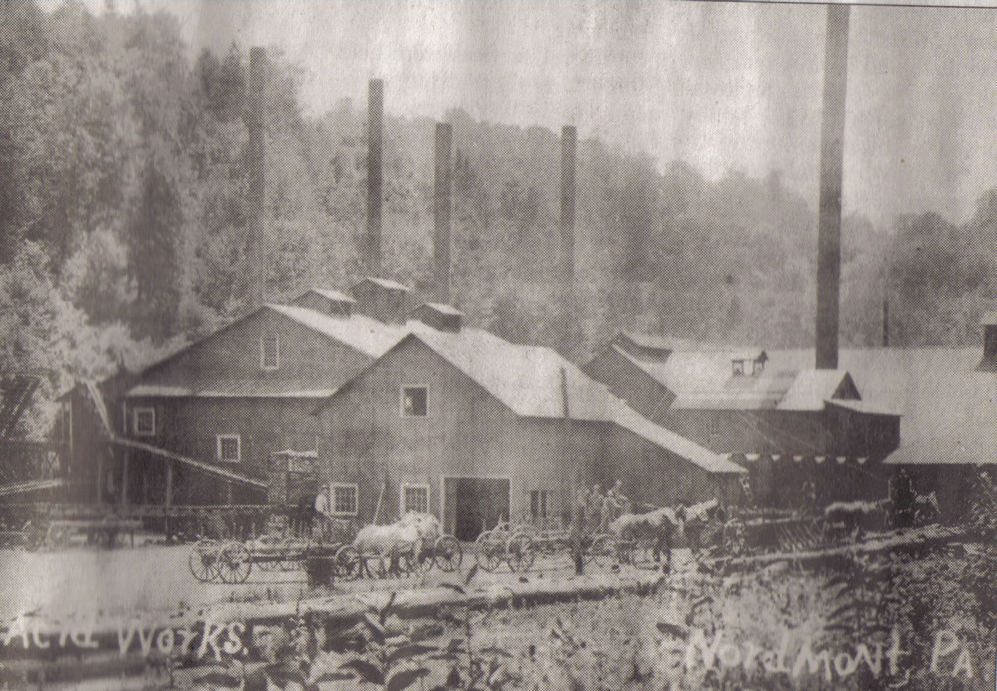

Nordmont Acid Factories

Strolling down memories lane with Frank Cox and Ralph King we recall

that the acid industry in Sullivan County has been reconstructed upon its

ruins. Thirty men return to their round

the clock labors seven day per week, converting two hundred and eighty cords of

four foot length hard wood into charcoal; the fumes and smoke from the baking

are distilled into wood alcohol, acitate, acitone and naptha, the charcoal

mixed with quick lime to become the base for smokeless powder and dynamite, the

liquids used in many industries including dyes.

Fifty

men with axes, saws and wedges and many teams of horses were employed the year

round in the vast timber tracts, cutting the wood and delivering it to points

along the twelve miles of standard gauge railroad used to transport the forest

product to the vast stock pile covering ten acres at Nordmont. The company